Introduction

In this article, we aim to demonstrate that the low prices of goods produced in the global South and the attendant modest contribution of its exports to the Gross Domestic Product of the North conceals the real dependence of the latter’s economies on low-waged Southern labor. We argue that the relocation of industry to the global South in the past three decades has resulted in a massive increase of transferred value to the North. The principal mechanisms for this transfer are the repatriation of surplus value by means of foreign direct investment, the unequal exchange of products embodying different quantities of value, and extortion through debt servicing.

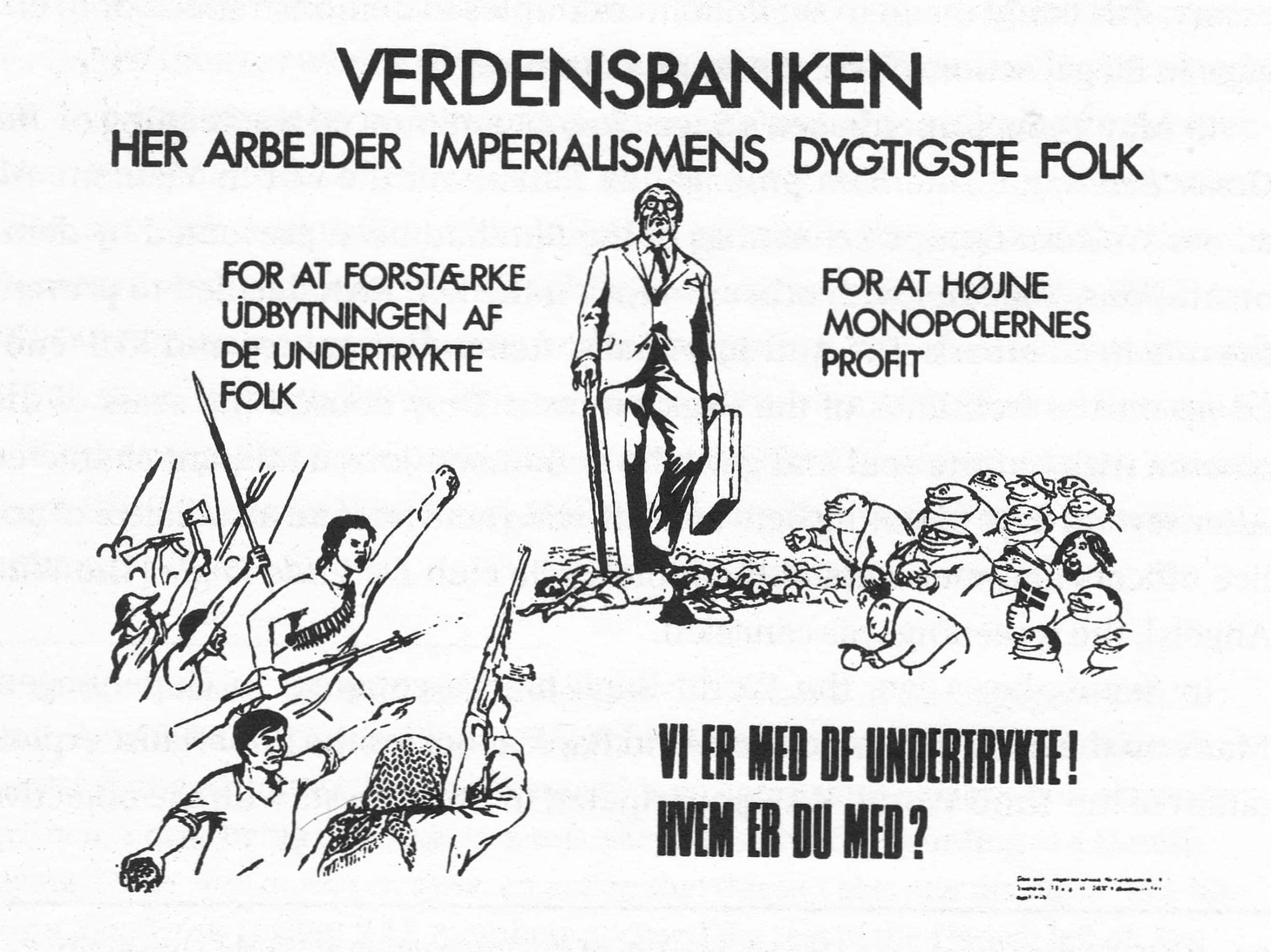

The incorporation of huge Southern economies into a capitalist world system dominated by global North-based transnational corporations and financial institutions has established the former as socially disarticulated export dependencies. The miserably low wage rates within these economies is predicated upon (1) the pressure imposed by their exports having to compete for limited shares of the largely metropolitan consumer market; (2) the drain of value and natural resources that might otherwise be used to build up the productive forces of the national economy; (3) the unresolved land question creating an oversupply of labor; (4) repressive comprador governments, who benefit from and accept the neoliberal order and are therefore unable and unwilling to grant wage rises for fear of spurring workers’ demands for greater political power; and (5) militarized borders preventing the movement of workers to the global North and, hence, an equalization of returns to labor.

The Imperialist Globalization of Production

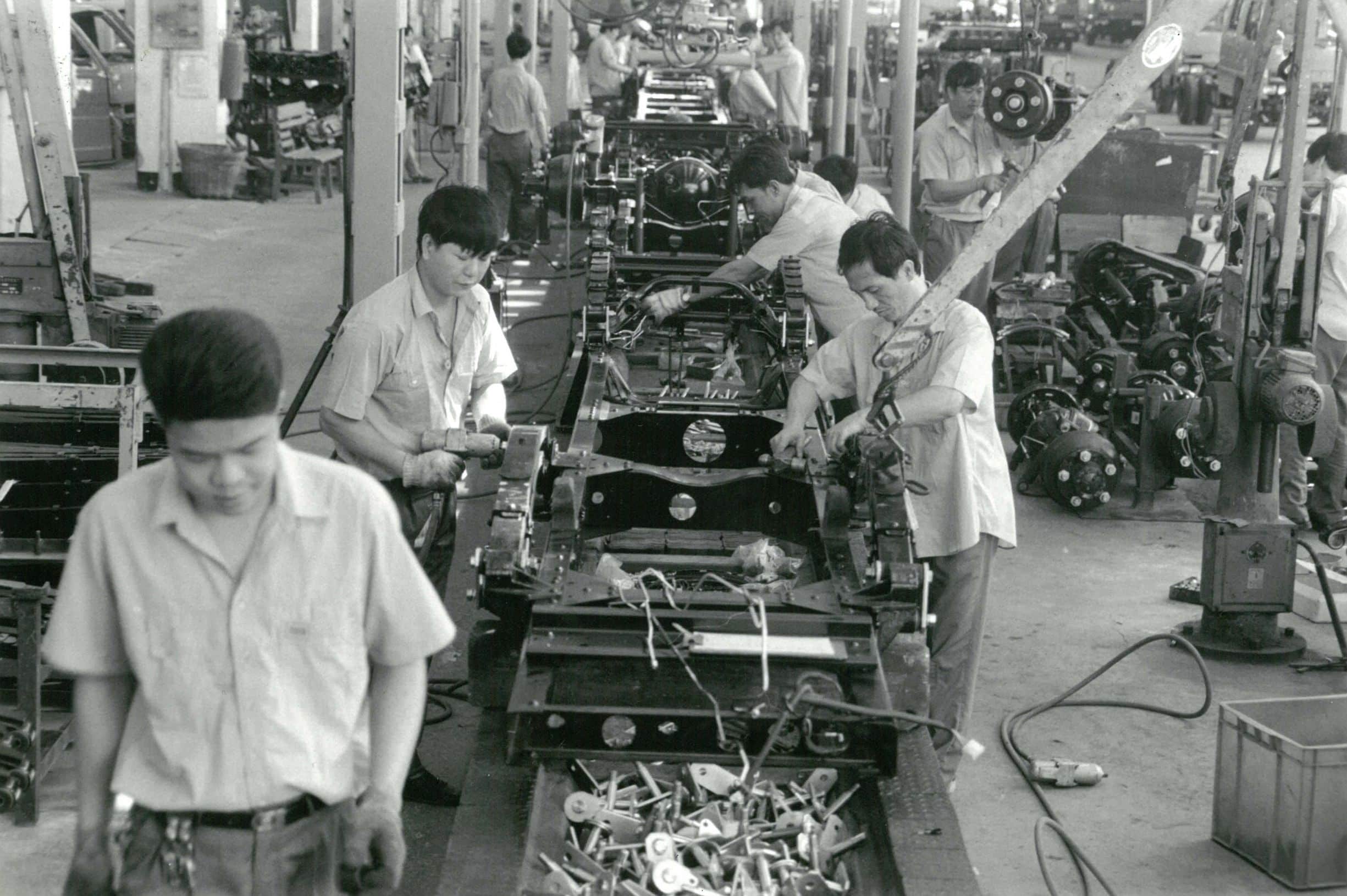

The debate on value transfer and unequal exchange is not new. Today, however, an increasingly large proportion of the goods the world consumes are produced in the global South. Production is not, as in the 1970s, limited to primary and simple industrial goods like oil, minerals, coffee, and toys. Rather, despite relatively low manufacturing “value added” (of which more below), virtually all types of industrial inputs and outputs are produced in the global South: these include chemicals, fabricated metal goods, machinery and electrical machinery, electronics, furniture and transport equipment to textiles, shoes, clothes, tobacco, and fuels.1 But why, and how, has this shift in the location of production happened?

The change in the international division of labor is a product of capitals’ perennial quest for higher profits and is based, first, on enormous growth in the number of proletarians integrated into the capitalist world system and, second, on the substantive industrialization of the South over the past three decades. This was made possible by the dissolution of the Soviet and Eastern European “actually existing socialist” economies, the opening of China to global capitalism, and the outsourcing of production to India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Brazil, Mexico, and other newly industrializing countries. The result was an increase of at least one billion low-wage proletarians within global capitalism. Today over 80 percent of the industrial workers in the world are located in the global South, while the proportion falls steadily in the North (see Chart 1). We may be living in post-industrial societies in the North, but the world as a whole is more industrial than ever.