Introduction

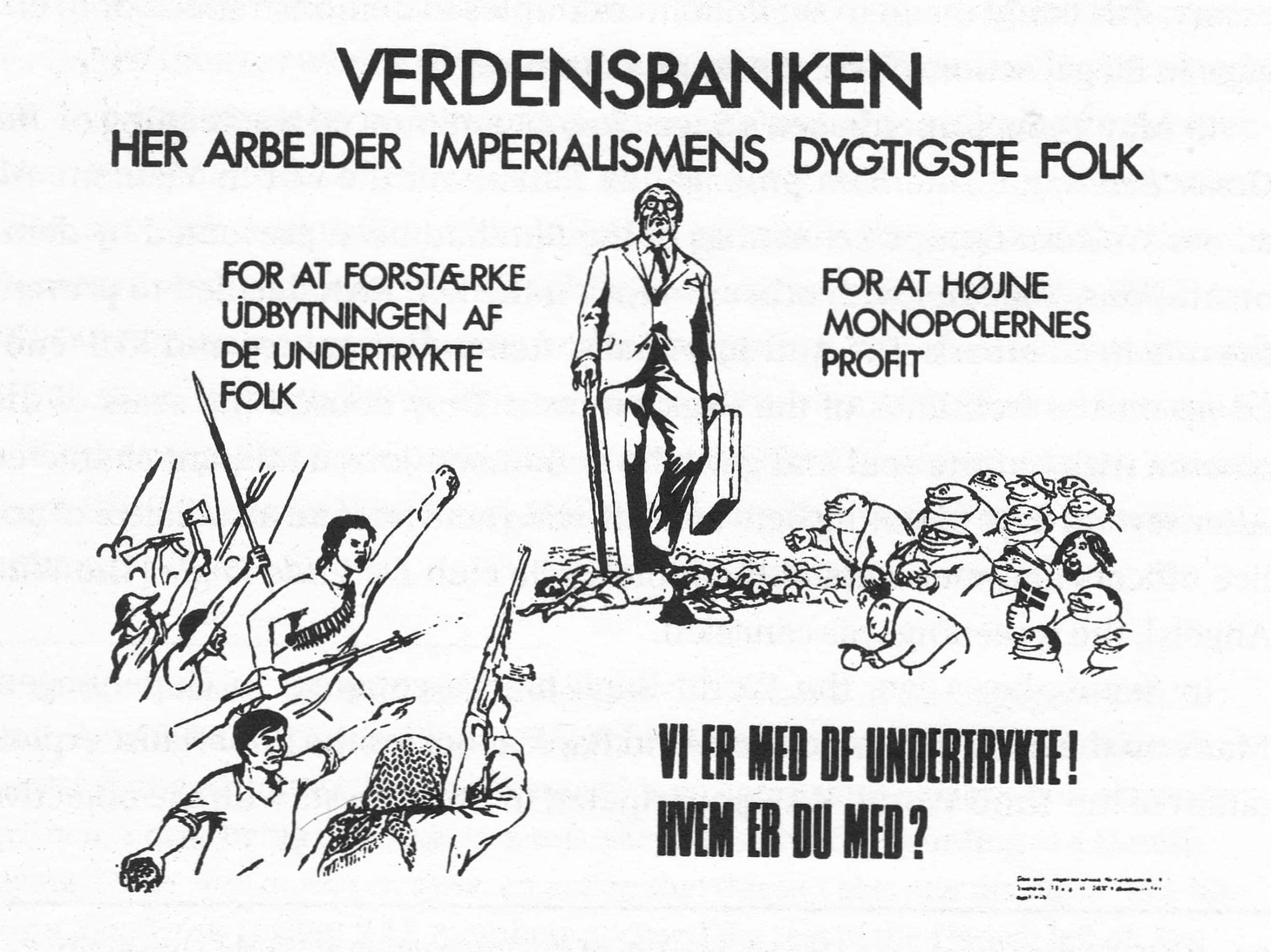

As it has been explained in the previous chapter, it was the internal contradictions of the capitalist mode of production which led to the recurring and increasingly serious crises of overproduction during the last half of the nineteenth century. The contradiction between productive forces and conditions of production showed itself as a disproportion between production and consumption, leading to overproduction. However, the contradiction changed its character around the turn of the century. Capitalism showed a new international mode of accumulation which was reflected by a growing domestic market in Western Europe and the United States. The basis of this development was an intensified exploitation of the colonies and other poor countries. One country’s exploitation of the other became a capitalist aspect of increasing importance, an aspect which is a characteristic of capitalism today.

An analysis of today’s capitalist mode of accumulation must therefore be based on a global point of view. Today’s capitalism is global and can therefore only be understood by means of a global analysis. Only then can we understand and explain the very different manifestations of capitalism in the rich and the poor countries. Danish welfare capitalism can only be understood through its connection with the exploitation of “the Third World” by the imperialist countries.

This global analysis of capitalism must be based on economic facts, because imperialism – which is the international form of the capitalist mode of production – is first and foremost an economic phenomenon characterized by the transfer of value from exploited countries to exploiting countries. The political, social, and cultural conditions are consequences of the imperialist economy. Other aspects are of course retroactive on the economy, but the economic forces are fundamental. Thus imperialism is not a policy which the imperialist countries can choose to pursue or to avoid. Ultimately, imperialist policy is a consequence of imperialist economy. An understanding of the political tendencies in the imperialist world must therefore be based on an understanding of its economic functions.

Marx himself never found time to work out a theory of the capitalist world market and international trade, even though it was part of his plan for the description of capitalism in “Capital”[1] Since Marx, various people have dealt with imperialism but have not been able to work out a theory applying to the world market. A marxist theory of this phenomenon was not framed until the appearance of Arghiri Emmanuel’s theory of “Unequal exchange”.[2] In this theory Emmanuel displays the mechanisms by means of which value is transferred from one country to another. His theory of unequal exchange is based on Marx’s interpretation of the law of value. Therefore, we shall summarize below the part of Marx’s theory which is necessary for understanding the theory of unequal exchange.

The Capitalist Mode of Accumulation

The Commodity – The Value of the Commodity is a Social Relation

Marx starts his analysis of the capitalist mode of accumulation from an analysis of the commodity. A commodity has two properties: use-value and exchange-value. The use-value means that the commodity can satisfy physical or psychical human wants; the exchange-value is the quantitative relation in which various use-values are exchanged.

A commodity is a product of human labour, made by an independent producer with the intention of exchanging it. Therefore, not all products of labour are commodities. If the product is exclusively made for the producer himself and is thus not exchanged, then it is no commodity, since it has only a use-value, and no exchange-value. Commodity production being production with a view to exchange, a product is considered a commodity because of its social properties, not because of its physical characteristics. Whether an object is a commodity cannot be definitely determined until it is put on the market to be exchanged.

The exchange relation between different commodities varies according to the circumstances under which the exchange occurs. It may for instance vary with time and place. Commodity exchange may thus immediately appear to be rather accidental. However, this is not the case. The exchange-value actually does reflect the common character of the commodities: the fact that they are products of human labour. The exchange-value is a manifestation of the value which the commodity has by virtue of being a product of human labour. What is actually compared at the commodity exchange is not the exchange-value itself, but the human labour inherent in the commodity. Thus commodity exchange is not a relation between objects or things. A commodity exchange reflects human relations between producers, i.e. social relations. This exchange of values appears as a relation between things, but it is a social relation.

Engels writes:

Political economy begins with commodities, with the moment when products are exchanged, either by individuals or by primitive communities. The product being exchanged is a commodity. But it is a commodity only because of the thing, the product being linked with a relation between two persons or communities, the relation between producer and consumer, who at this stage are no longer united in the same person. Here is at once an example of a peculiar fact, which pervades the whole of economics and has produced serious confusion in the minds of bourgeois economists: economics is not concerned with things but with relations between persons, and in the final analysis between classes, these relations, however, are always bound to things and appear as things.

(Engels, Karl Marx, MECW, v. 16, p. 476. )[3]

To the dual character of the commodity corresponds a dual character of the labour. Use-value is based on actual labour: carpenting, forging, weaving etc., the use-value and the actual labour being of a qualitative nature. Exchange-value is based on abstract labour – on the consumption of human labour-power – which is of a quantitative nature. Thus abstract labour forms the basis of the value of the commodity which is compared to the value of other commodities when exchanged.

Commodity Production – Generally Defined

Commodity production proper requires such a development of the social division of labour that an exchange of products is necessary. The individual producer expects that there is a social need for the produced use-values.

A commodity is thus a product of human labour, produced with the intention of being exchanged with other products of human labour. But it is not until the product is placed on the market that it can be seen whether the labour which was consumed in the production can be realized, i.e. whether it has a use-value to other people. So, society must consider the produced commodity to be necessary. There must be – either immediately after the production or some time in the future – a market able to buy it, otherwise the labour consumed has been wasted, from a social point of view, without creating any value.

Simple Commodity Production

The Producer Owns His Own Means of Production

The Commodity is Exchanged at Its Own Value

The social phenomenon which Marx calls simple commodity production belongs to a certain historical period before capitalism. The production of commodities is much older than capitalism. Commodity production existed in the slave society as well as in the feudal society. Early commodity production was characterized by the producer owning his own means of production, and his products. The producer, for instance a farmer or an artisan, thus acted alone in the production. At that time the exploitation of other people through wage labour was not, yet pronounced. Labour-power was not yet a commodity.

In a society with simple commodity production there is a tendency towards the commodities being exchanged at their value. This means that they are exchanged in accordance with the amount of abstract human labour contained in their production within the socially necessary labour-time – i.e. within the production-time required under normal conditions, with average degree of skill and intensity and with the technology normally used in the society in question. And, finally, society must regard the product as a necessity.

Commodity Production Under Developed Capitalism

Producer and Means of Production Separated

Commodities are Exchanged at the Prices of Production

In the case of simple commodity production the producer owns his own means of production. In the case of developed capitalism the producer owns neither the means of production nor the product. Thus the proletariat and the bourgeoisie tome into existence. The arrival of these classes is discussed shortly below.

Primitive Accumulation

Marx and Engels write in the Manifesto of the Communist Party:

We see then: the means of production and of exchange, on whose foundation the bourgeoisie built itself up, were generated in feudal society. At a certain stage in the development of these means of production and of exchange, the conditions under which feudal society produced and exchanged, the feudal organisation of agriculture and manufacturing industry, in one word, the feudal relations of property became no longer compatible with the already developed productive forces; they became so many fetters. They had to be burst asunder; they were burst asunder.

(Op. cit., MESW, p. 40.)[4]

The disintegration of feudalism and the creation of the prerequisites of the capitalist mode of production Marx calls “primitive accumulation” – primitive because the birth of capitalism cannot be explained by the law of accumulation of the capitalist mode of production itself. The accumulation of the values which constituted the primitive capital was not a result of capitalist exploitation, wage labour, but a result of actual violence and open theft. The creation of the proletariat was not a consequence of capitalism but a consequence of the historical background of capitalism, of its basis.

In “The so-called primitive accumulation” (Capital, v. I, part viii), Marx goes thoroughly into the question of what primitive accumulation contains. He describes it as the process creating the basic conditions of capitalist production: On the one pole the creation of “free” propertyless labourers, unencumbered with the means of production; on the other pole the creation of the owners of money, means of production and means of subsistence, whose only aim it is to increase the sum of value they possess or – in short the capitalists. The original capitals were mostly a result of the exploitation of the colonial areas.

Marx writes:

The discovery of gold and silver in America, the extirpation, enslavement and entombment in mines of the aboriginal population, the beginning of the conquest and looting of the East Indies, the turning of Africa into a warren for the commercial hunting of blackskins, signalised the rosy dawn of the era of capitalist production. These idyllic proceedings are the chief momenta of primitive accumulation. On their heels treads the commercial war of the European nations, with the globe for a theatre….

The different momenta of primitive accumulation distribute themselves now, more or less in chronological order, particularly over Spain, Portugal, Holland, France, and England. In England at the end of the 17th century, they arrive at a systematical combination, embracing the colonies, the national debt, the modern mode of taxation, and the protectionist system. These methods depend in part on brute force, e.g., the colonial system. But they all employ the power of the State, the concentrated and organised force of society, to hasten, hot-house fashion, the process of transformation of the feudal mode of production into the capitalist mode, and to shorten the transition. Force is the midwife of every old society pregnant with a new one. It is itself an economic power.

(Capital, v. I, p. 703.)

As the primitive accumulation and the exploitation of the colonial areas were a condition of the break-through of capitalism, the creation of a proletariat was also a necessity. That means the existence of a class of “free” labourers, “free” in a double sense. Firstly, they must be able to sell their labour-power freely and not as slaves or bondsmen be tied to a certain production. Secondly, they must be free from any rights of property to the means of production, and not work as the peasant or the artisan with their own means of production. They are to be free and idle on the market and thus forced to take part in the capitalist production as wage labourers to secure their subsistence. And so two basic classes arise under capitalism: the bourgeoisie and the proletariat; the capitalists with the capital, hence with the means of production, and the proletariat, deprived of this means of production, with only its labour-power to offer. Under capitalism, labour-power has thus also become a commodity.

Labour-Power – Its Value and Price

In several ways labour-power is not a common commodity. Its price, wages, is not fixed by economic laws to the same extent as the price of other commodities. Unlike the prices of other commodities, wages are fixed primarily by the class struggle in society. However, it is not only the class struggle which determines wages. Thus Marx distinguished between two elements in the case of the determination of the value of labour-power. Partly the physical reproduction costs of labour-power and partly what he describes as the historical and moral element. The reproduction costs of labour-power means the price of the commodities which are necessary if the worker – and the working class as a whole – is to continue his work, his subsistence, and reproduction. It is a question of basic food, clothing, and housing. If the labourer is only paid a sum which covers the physical reproduction costs, it is described as subsistence wages.

All attempts to determine the price of labour-power from the physical reproduction-costs alone have hitherto failed. For wages to be determined by those circumstances a free labour-market would be necessary, and such a free market never existed, generally speaking, except perhaps for a short while immediately after the establishment of the capitalist system. The complex rules and regulations of the preceding feudal system, and the class struggle that was to follow, left very little room for any free labour-market.

Besides the prices of the purely physically determined means of subsistence, the value of the labour-power is determined by the “historical and moral element”.

Marx says:

On the other hand, the number and extent of his so-called necessary wants, as also the modes of satisfying them, are themselves the product of historical development, and depend therefore to a great extent on the degree of civilisation of a country, more particularly on the conditions under which, and consequently on the habits and degree of comfort in which, the class of free labourers has been formed. In contradistinction therefore to the case of other commodities, there enters into the determination of the value of labour-power a historical and moral element. Nevertheless, in a given country, at a given period, the average quantity of the means of subsistence necessary for the labourer is practically known.

(op. cit., p. 168. )

The factors which determine the value and price of labour-power – namely the class struggle and the reproduction costs – interact during the course of development. In the same way, a dialectic relationship exists between the value of labour-power and the price of labour-power, i.e. wages. The value of labour-power is thus in itself indirectly determined by the wages. Even though the value also determines the wages, the wages retroact on the value, as the working class gets the possibility of including more commodities in its reproduction when it obtains higher wages through the class struggle. When the higher wages have existed for some time, this price of labour-power becomes equivalent to the value of labour-power.

Thus “the historical and moral element” – which means the class struggle and its entire historical and economic basis – determines to a high degree the wage-level under capitalism. However, the historical and moral element is also influenced by earlier wage-levels.

If we assume that wages fluctuate around the value of labour-power, this, means that the value of labour-power differs throughout the world. Where comparatively high wages are paid, the value of labour-power is at a comparatively high level. Conversely, the value of labour-power is at a comparatively low level where comparatively low wages are paid. Consequently the value of labour-power is at a high level in the wealthy imperialist countries and at a low level in the exploited countries in the Third World. Throughout a long historical period, a high wage level in the rich countries has resulted in a high level of reproduction costs. Reproduction costs have in these countries included many consumer goods of various kinds and are consequently an expression of a high value. The low wage level in the Third World means reproduction costs at a low level and thus it reflects a low value. The reproduction costs in the Third World include mainly physical subsistence goods. If we define the value of labour-power in this strictly theoretic way from a national point of view, it is because: It is a fact that the price level of the commodity labour-power differs very much in the world.

Therefore, there is no moral evaluation contained in the concept of value in this connection. It is a strictly economic definition. That labour-power is paid according to its value has nothing to do with fairness.

Of course the use-value of labour-power – the ability to create value – is not influenced by these differences in the value of the actual labour-power. Labour performed with the same qualifications is equally productive no matter where the labour is performed and no matter what value the actual labour-power has. Why should docker in Esbjerg in Denmark create more value than a docker in Bombay in India just because the Danish docker’s wages are 50 times higher? With the same qualifications and the same intensity; the value of their work must be the same no matter what the value of their labour-power might be.

Thus the size of the wages is dependent on the relative strength between the classes and on the position of the country in the world. Consequently, the market for labour-power differs from the normal commodity market. There are norms, rules, laws, and union regulations as to the length of the working day, working conditions, overtime, minimum wages, piece rates etc. There are comparatively fixed limits to the variability of wages within one country. These limits do not immediately reflect economic laws, but rather political conditions. The internationally different course of the class struggle has created considerable differences in wages internationally. However, within the individual country – particularly the imperialist countries – there is a tendency towards an equalization of the wage level. This national tendency towards equalization is partly due to the comparatively high degree of, labour mobility within the countries and partly to political interventions.[5]

A similar tendency cannot be seen internationally. On the contrary, the differences in wages between the imperialist countries and the exploited countries have increased. The price for the commodity labour-power has not followed the general tendency towards the setting of one world market price. Wages vary relatively little within a given period but very much from place to place. There are subsistence wages in the Third World and comparatively high wages in the imperialist countries. On the other hand, the price of most commodities varies enormously from time to time but comparatively little from place to place in the world. For example the price of topper or wheat may vary considerably from month to month or even from day to day, but geographically the price varies only little. At a specified time there is a world market price. The opposite applies in the cause of wages.

Emmanuel writes:

From remotest antiquity to the beginning of the 19th century, the wage has, in real terms, hardly varied in any country; from the beginning of the 19th century up to the present it has, in certain countries, moved slowly and steadily upwards. Such a constancy in certain periods or certain countries, such an evenness and duration of a one-dimensional movement in certain other periods and other countries, are contrary to the endogenous economic determinations which are plastic and multiform. An extra-economic (institution) vector alone can generate them.

At any rate, on the international plane, the multiplicity of wage rates is inconsistent with the existence of a market since the essential function of the market is precisely to secure one price for each item. Now in the case of wages, this disparity continues without the slightest attenuation, even when, here or there and in certain epochs, the labour-factor enjoys a relatively important mobility. Neither the great immigration of Europeans into the United States during the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, nor the contemporary considerable immigration of North Africans, Portuguese, Greeks, etc., into the developed countries of Western Europe after the last war, have given rise to the slightest tendency towards the equalization of wages between the countries of origin and the host countries.

… There is no relevance between the conjunctural fluctuations of employment in different countries and the comparative rates of wages in these same countries. For example: during the 1929-34 crisis, unemployment in the United States was 36.47% of the active population against 13.42% in France and only 7% in Italy. Yet the American wage remained, during the worst of the crisis, two to three times that in France and three to four times that in Italy.

We can conclude that the determination of wages is more a political than an economic process. Its variations reflect the fluctuations of the relations of power between social classes. This extra-economic institutional determination makes possible a lasting gap between the price and value of labour power.

However, these two magnitudes continue to be connected to each other in a dialectical interaction. A wage greater than the value of labour power, if it prevails for a long time, ends by driving upwards this value itself, since the extra consumption which it allows ends by being transformed into vital needs – what Marx calls a second nature – and, hence, by being incorporated into the real cost of reproduction of the labour force.

(Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange Revisited, pp. 49-50.)

Wage labour must be regarded as it is: a social relation in which classes fight for their interests – i.e. the struggle for the division of the social product into wages to the labourers and profit to the capitalists. Thus wages constitute a part of the social product and their size reflects the relative strength between the classes and the economic basis on which the class struggle takes place.[6]

Productivity and Wages

One of the most popular explanations of the international differences in wages is that they are based on corresponding differences in productivity. There are even people who claim that the workers in the developed, imperialist countries – because of their high degree of productivity – are more exploited than the proletariat in the Third World.

Their argumentation can be summed up as follows: Generally, the rate of productivity in the imperialist countries is much higher than in the Third World. This high rate of productivity results in a fall in the value of the commodities which form part of the labourers’ consumption. Consequently, the necessary labour-time decreases – i.e. the time required for the production of the commodities necessary for the reproduction of labour power – in proportion to the surplus labour. The high wages which can buy many commodities, do not reflect a higher value but only a higher rate of productivity. The increasing wages have not even been able to keep pace with the increasing productivity. Surplus labour accounts for an increasing part of the working day in proportion to the necessary labour. Thus the working class in the imperialist countries enjoys an increasing standard of living while it is exploited more and more at the same time. However, in the Third World the rate of productivity is lower for the products included in the consumption of the working class. This means that the necessary labour-time accounts for a larger part of the total labour-time than in the imperialist countries.

Thus, in spite of the wretched conditions, the labour power in the Third World is less exploited than the labour-power in the imperialist countries. This is due to the difference in the rate of productivity in the world. A high rate of productivity means high wages, a low rate of productivity means low wages.

In this chapter we shall deal with the above assertion from a theoretic point of view. (In Chapter 4 we shall deal with it empirically.)

A Marxist definition of productivity must strictly distinguish productivity from the terms intensity and profitability. These three terms are often mixed up. The bourgeois economists mostly focus on “output per labourer” measured by the quantity of commodities produced or by the quantity of profit created. Whether an increased “output per labourer” is due to increased price on the products, new more efficient technology or harder wear of the labour-power is not so important to them. Also many Marxists confuse intensity (the rate of wearing out the labour-power) and productivity (the efficiency of the machines). by defining productivity as “number of produced commodities per unit of time”. They are unable to distinguish between the results of new technology or of harder wear of the labour-power.

To make it possible to distinguish the influence of the different components, we will define the terms as follows:

Profitability is the proportion between the market price and the price of production of a given commodity. An increasing market price or a decreasing price of production results in higher profitability.

Intensity is the rate of consumption of the labour-power. Higher intensity means faster wearing out of the labourers, and more produced commodities per unit of time by the same means of production. (The exploitation of women workers in South Korea is an example of high intensity and fast wearing out of labour power.)

Productivity is determined by the efficiency of the technological facilities and by the organization of the production. Improving the technology and/or the organization, keeping intensity the same, results in a production of more commodities per unit of time.

Both increased intensity and increased productivity results in creation of more use-value per unit of time. But only increased intensity creates more value per unit of time. Increased productivity just means the production of a greater quantity of commodities containing the same value.

In his analysis of piece rates and piece payment (Capital, v. I, ch. 19), Marx shows how the apparent connection between productivity and wages is false, since piece rates are a concealed form of time wages. If the piece rate for one unit in a certain enterprise is for example $4 – and the average wage for the labour in question is $40 per day, – the piece rate only reflects that the capitalist has calculated that an average worker is able to produce 10 units per day. The worker who is able to produce 12 units with the same machinery, tools, etc. and who gets $48 – does not work more productively but more intensively and therefore demands higher reproduction costs. If new and more productive machinery suddenly made it possible for the average labourer to produce 20 units instead of 10, this would not result in a twofold increase of the day’s wages.

This thought is absurd under capitalist conditions of production. What would happen is that the piece rate would be reduced twofold. The wages, are not the price for the result of the labour, but the price for the labour-power.

Engels writes in a letter to Lafargue:

… in what respect the wage worker gains an advantage in seeing his productivity increase, when the product of that productivity does not belong to him and when his wage is not determined by the productivity of the machine.

(Engels-Lafargue Correspondence, v. I, p. 233.)

Improvements in productivity are a result of improved technology of the capitalist production apparatus. A gain which is a result of improvements in productivity goes to the capitalist as profit, perhaps surplus profit, for a short period. A profit in which the labourer has no claim to share under capitalist conditions of production. The value and payment of the labour-power do not depend on whether the labourer operates an expensive, highly productive plant or a screwdriver. No matter how big the difference in productivity is, it cannot be a result of the labour-power in itself. In the case of an equal amount of used labour-power – i.e. an equal wear of muscles and nerves and equal education and qualifications – an unequal result can only be explained by other factors, i.e. the quality of the means of production which is paid through profit. The assertion that the wages of agricultural workers are determined by the fertility of the soil, and the wages of the industrial workers by the size and quality of the machinery is not only absurd, but has nothing to do with reality. In a capitalist society, the product of the soil or of the machinery belongs to the landowner or the industrial capitalist. Only in the case of independent producers, who own their land and tools, is there a connection between the productivity and the wages of the labour.

The productivity of the labourers’ work does not influence his wages. However, Marx believes that an increased productivity in the sectors which are included in the determination of the value of the labour-power may have an influence – in a downward direction. But if we assume it to be in an upward direction it is difficult to understand why the working class in the Third World does not benefit from the productivity increases to the same extent.

… one could not see why the same quantity of labour of the same qualification, incorporating the same learning and training should be paid ten times more or less according to whether it is supplied some miles on this or the other side of the American-Mexican border and according to whether the name of the vendor is John or Fernandez. Of all monopolies, this one, grounded on a passport or a birth certificate, seems to me the most “un-ethical”.

(Emmanuel, Unequal Exchange Summary, p. 25.)

The commodities which represent the reproduction costs of the working class do more or less cost the same all over the would. Generally speaking, the costs of maintaining a living standard as a Danish worker are the same in Denmark, Tanzania, Brazil, or Hong Kong. The price for one kilo of wheat, one kilo of meat, one watch, or a transistor radio varies by 10, 20 or 50 per cent from country to country. However, the wages are 5, 10, 20 or 50 times higher in the imperialist countries.

If there were a connection between productivity and wages in an enterprise, it would mean that the labourer and the capitalist would find it in their common interest to improve productivity. The capitalist would do better in the competition and the labourer would obtain a wage increase. Marx attacked this point of view. The capitalist does not buy the labour but the labour-power. The labour-power is not paid according to the result of the labour. A surplus arising from a productivity increase belongs to the capitalist.[7]

Historically, the connection between productivity increases and wages has not been to the labourers’ advantage. This is one of Marx’s conclusions. He dealt very thoroughly with the relation between the development of the productive forces, the productivity increase, and the effect of it on the standard of living of the working class at his time. He describes how the accumulation of capital, the expansion of productive forces, and the productivity increase create the industrial reserve army, decrease the wages and decrease the standard of living.

The greater the social wealth, the functioning capital, the extent and energy of its growth, and, therefore, also the absolute mass of the proletariat and the productiveness of its labour, the greater is the industrial reserve army. The same causes which develop the expansive power of capital, develop also the labour power at its disposal…. The more extensive … the industrial reserve army, the greater is the official pauperism. This is the absolute general law of capitalist accumulation.

In the same connection, Marx gives some concrete examples of this. During the period 1846-66 – in which the productive forces advanced considerably in Britain – the standard of living decreased.[8] Thus, according to Marx there is no internal, regular connection between development of productivity and the standard of living which create wage increases. Actually, the considerable increase in productivity which took plane from the break-through of industrial capitalism at the end of the eighteenth century, did not at all mean wage increases or improved standard of living for the working class. The first period 1790-1845 meant a direct decrease in the standard of living. Not until the abolition of the Corn Laws in 1846 did the working class obtain its earlier standard of living.[9] The incipient wage increases in the 1870s were not based on productivity increases either, but were a result of the formation of a new economic world order – imperialism.

We conclude that the alleged economic connection between productivity increases and wage increases is wrong. What determines the wages is the class struggle and the possibilities of wage variation which the international position of the national economies can offer.[10]

The Use-Value of Labour-Power

To the capitalist the commodity labour-power has one quality which is different from the qualities of all other commodities. It can be used for the production of commodities, the value of which is higher than the value of the components used in the production. In order to use the labour-power, the capitalist must possess the means of production.

The Circulation of Capital

The capitalist invests partly in buildings, machinery, raw material etc., in short: the production apparatus. This part of the capital is called constant capital, because it does not differ in value during the accumulation. Partly the capitalist invests in labour-power. This part of the capital is called variable capital, because it forms the basis of the creation of new value in the production. Thus the commodities which the capitalist acquires by investments are divided into two main parts which both are equally vital: variable capital and constant capital.[11]

The circulation of capital consists of a production of and a trade in commodities. These two aspects of the circulation are interdependent: no production without trade, and no trade without production.

The first stage in the circulation of industrial capital is the trade in commodities, when the capitalist buys labour-power and the means of production. The next stage, the production – which is the basis of the increase in value – is the consumption of the purchased commodities, This is the production of commodities which the capitalist assumes that he can sell at a higher price than the amount of the original investment.

The value of the labour-power and the value created by the labourer during the working process are two different quantities. The created value, the increase in value, consists of the value which exceeds the value of the labour-power. Or in other words: the value which exceeds the “time” when the labourer has performed a piece of work corresponding to the work necessary to produce the commodities which the labourer buys for his wages. Only the living labour, labour-power, can be the source of created value. The means of production, which the capitalist bought to start his production, change their shape (for example from leather to shoes), but their value does not change. They maintain their value, which is transferred to the finished commodities to the same extent as the means of production are used during the production.

The following stage is again in the trade in commodities where the appropriation of the value takes place. In order to make it possible for the capitalist to secure all of the created value, it is important that the finished commodities can be sold at their value. This means the total capital outlay for variable and constant capital plus the surplus value. If he succeeds, the capitalist has increased the original capital by the surplus value. It can be used productively – i.e. for a new, expanded circulation – or unproductively, for consumption.

The total circulation of capital appears as follows:[12]

Thus the circulation of capital, the course of capitalist accumulation, consists of a production (where the material goods are created) and of a trade in commodities (where the commodities are distributed and appropriated by the classes). These two elements form a whole.[13] Therefore, a correct understanding of capitalist accumulation is only possible if all its elements are analysed, their connection and mutual influence.

Surplus-Value

The surplus-value is the value created by the labourer exceeding the value of his own labour-power. Theoretically, the working-day in a capitalist enterprise can be divided into two parts: the necessary labour-time when the labourer reproduces the value of his own labour-power, and the surplus labour-time when the surplus-value is created.[14]

The Rate of Surplus-Value

The rate of surplus-value is the ratio of surplus-labour to the necessary labour. Expressed in terms of value, it is the ratio of the value of labour-power to the surplus-value or the ratio of variable capital to surplus-value:

Thus the rate of surplus-value reflects the rate of exploitation of the labour-power. The constant capital does not influence the value which is created. Whether it forms a large or a small part of the production does not influence the rate of surplus-value.

Within the frontiers of a country, there is a tendency towards an equalization of the rate of surplus-value in the various spheres of production, caused by the movements of the labour-power, which will seek employment where the rate of exploitation is lowest.

Marx writes:

This (the equalisation of the rate of exploitation) would assume competition among labourers and equalisation through their continual migration from one sphere of production to another.

Marx meant that this tendency to equalisation made itself felt in the developed capitalist countries:

We see at a glance that, in our capitalist society, a given portion of human labour is, in accordance with the varying demand, at one time supplied in the form of tailoring, at another in the form of weaving. This change may possibly not take place without friction, but take place it must. [15]

(Quoted from V.M. Dandekar, “Bourgeois Politics of the Working Class”, Economic and Political Weekly, vol. xv, no. 2, 12 Jan. 1980.)

Cost-Price

The individual capitalist is not interested in surplus-value and the rate of surplus-value. He is not interested in knowing how much surplus-value he forces from the labourer, but he is interested in how much profit the total amount of invested capital yields.

Therefore, what actually interests the capitalist is the production costs of the finished commodities – their cost-price.

The value of every commodity produced in the capitalist way is represented in the formula: V=c+v+s. If we subtract surplus-values from this value of the product there remains a bare equivalent or a substitute value in goods, for the capital-value c+v expended in the elements of production…. This portion of the value of the commodity, which replaces the price of the consumed means of production and labour-power, only replaces what the commodity costs the capitalist himself. For him it, therefore, represents the cost-price of the commodity.

(Marx, Capital, v. III, p. 25-6. )

How this cost-price is distributed between constant and variable capital does not interest the capitalist. To him the profit is the yield of the aggregate capital.

In its assumed capacity of offspring of the aggregate advanced capital, surplus-value takes the converted form of profit. (ibid., p. 36.)

The Rate of Profit

The ratio of the surplus-value to the aggregate advanced capital is defined as the rate of profit:

Theoretically, the rate of profit of the individual capitalist depends therefore partly on the rate of surplus-value and partly on the ratio of the constant capital to the variable capital. An increase or fall in the rate of surplus-value results in a similar tendency for the rate of profit. The proportion of constant to variable capital is also defined as the organic composition of capital. This proportion of values is based on the technical composition of labour-power and means of production, respectively, in the given line of industry. Capital has a low organic composition if the variable capital forms a large part of the aggregate capital. Conversely, capital has a high organic composition if the constant capital forms a large part.[16]

In the following example, in which the same rate of surplus-value and the same turnover time are used,[17] it is shown how the organic composition of capital effects the rate of profit. The higher the organic composition, the lower the rate of profit, and the lower the organic composition, the higher the rate of profit.[18]

Table 3.1

| Aggregate | Rate of | Surplus- | Value of | Rate of | |

| capitals | surplus- | value | product | profit, % | |

| value, % | |||||

| C=c+v | s/v | s | V=c+v+s | p’=s/C | |

| I | 80c+20v | 100 | 20 | 120 | 20 |

| II | 70c+30v | 100 | 30 | 130 | 30 |

| III | 60c+40v | 100 | 40 | 140 | 40 |

| IV | 85c+15v | 100 | 15 | 115 | 15 |

| V | 95c+5v | 100 | 5 | 105 | 5 |

(Source: Capital, v. III, p. 155.)

The Creation of an Average Rate of Profit Between the Branches of Production

From Table 3.1 it can be seen how equally big capitals with different organic composition obtain different surplus-values, which theoretically result in very different rates of profit from equally big capitals. However, this tendency cannot be seen in reality. If it could be seen, it would mean that the capital would flow to the branches of production with a low organic composition – where the variable capital is a comparatively large amount of the aggregate capital – and away from branches of production with a high organic, composition where the constant capital constitutes a comparatively large part. However, this is not the case. The capital does not particularly seek branches of production with a low organic composition. We know from the real world that substantial differences in the average rates of profit for the various lines of industry do not exist – apart from transitory, accidental differences which equalize each other in the long term. They cannot exist without abolishing the capitalist system. Therefore, the question is how and why this equalization takes place.

The average rate of profit is formed by the capitalists’ continuous search for higher rates of profit. If a heavy demand for the commodities of a certain line of industry arises, the price for these commodities will increase and consequently the rate of profit within that sector will increase. This will result in capital flowing to that sector to obtain a share of the higher rate of profit. This leads to an increased production of the commodities of the sector which again leads to a saturation of the social wants, perhaps to overproduction, and thus to a fall in prices, which means a lower rate of profit – and consequently a flight of capital from the sector. Thus the difference in the rates of profit from one line of industry to the other is the basis of continuous capital movements and consequently of a tendency towards an equalization of the rates of profit. Thus the competition between the capitals tends towards equalizing the rates of profit of the various lines of industry to an average rate of profit so that equally big capitals yield equally big profits, no matter where the investment is made, and no matter how the capital is distributed between constant and variable capital. Then the average profit can be defined as the profit which, according to the general rate of profit, goes to a capital of a given size no matter how the organic composition is.

This means that the original commodity values are turned into prices of production. The price of production of a commodity is equal to its cost-price plus the share of the annual average profit of the aggregate capital invested (not merely consumed) in its production (in accordance with the conditions of turnover). In other words:

Price of prodiction = cost-price + the total used capital x average rate of profit

The price of production must not be confused with the market price.[19] It is a coincidence if they are identical. During the historical period of simple commodity production, the commodity prices fluctuated around the commodity value. But under developed capitalism the price of production forms the centre of the fluctuation for the current market prices. Thus the price of production for the individual commodity is not the same as the value of the individual commodity. But the total sum of the prices of production will equal the sum of the commodity values – just as the sum of the profits will equal the total surplus-value.

Let us see how the formation of an average rate of profit influences Table 3.1. In Table 3.2, each aggregate capital is still 100, the rate of surplus-value is constant: 100%. We assume that the whole capital turns over in one circulation. The new thing in Table 3.2 is the formation of the average rate of profit:

(20%+30%+40%+15%+5%) /5=22%.

Taken together, the commodities are sold at 2+7+17=26 above, and 8+18=26 below their value, so that the deviations of price from value balance out one another through the uniform distribution of surplus-value, or through addition of the average profit’ of 22 per 100 units of advanced capital to the respective cost-prices of the commodities I to V…. The prices obtained as the average of the various rates of profit in the different spheres of production, added to the cost-prices of the different spheres of production, constitute the prices of production. They have as their prerequisite the existence of a general rate of profit, and this again, presupposes that the rates of profit in every individual sphere of production taken by itself have previously been reduced to just as many average rates. These particular rates of profit = s/C in every sphere of production, and must … be deduced out of the values of the commodities. Without such deduction the general rate of profit (and consequently the price of production of commodities) remains a vague and senseless conception. Hence, the price of production of a commodity is equal to its cost-price plus the profit, allotted to it in per cent, in accordance with the general rate of profit, or, in other words, to its cost-price plus the average profit. (Marx, Capital, v. III, p. 157.)

Table 3.2

| Total | Sur- | Value | Average | Price | Devia- | |

| capital | plus- | profit- | of pro- | tion of | ||

| value | rate, % | duction | PP from | |||

| C | s | V | P’ | PP | value | |

| I | 80c+20v | 20 | 120 | 22 | 122 | +2 |

| II | 70c+30v | 30 | 130 | 22 | 122 | -8 |

| III | 60c+40v | 40 | 140 | 22 | 122 | -18 |

| IV | 85c+15v | 15 | 115 | 22 | 122 | +7 |

| V | 95c+5v | 5 | 105 | 22 | 122 | +17 |

[20]

As can be seen from the table, the organic composition of the various capitals varies widely. This means that each of them employs very different quantities of human labour. Thus the basis of different quantities of surplus-value within the various lines of production is formed. However, the surplus-value does not necessarily fall to the line of production where it was created. By means of the equalization of the rate of profit there is a transfer of value from one line of production, which is below average, as to organic composition, to the lines of production which are above.

This transfer of value is of no interest to the capitalists. They do not observe it. The individual capitalist does not care how high the rate of surplus-value is in the enterprise or line of production in question. The capitalist is interested in the profit, and because of the equalization of the rate of profit, it is evenly distributed between all capitals, no matter how the organic composition is.

This transfer of value is called “unequal exchange” by some economists.[21] However, there is nothing “unequal” about this transfer, as it is a condition of the actual function of capitalism. This equalization of the rate of profit makes it profitable for the capitalist continuously to improve his production apparatus – indeed it forces him to do so in order to survive the competition. Thus capitalism gets the dynamics, the capability to improve the productive forces. If we imagine that the commodities were sold at their value instead of at a price which fluctuates around the price of production, it would lead to a stop in investments, in mechanization and in productions of a highly organic composition, whereas labour-intensive productions with much variable capital and consequently with much surplus-value would gain ground. Chemical industries would die out and wood-carving would flourish.

The Conditions for an Equalization of the Rate of Profit Nationally

Marx describes these in Capital:

Now, if the commodities are sold at their values, then, as we have shown, very different rates of profit arise in the various spheres of production, depending on the different organic composition of the masses of capital invested in them. But capital withdraws from a sphere with a low rate of profit and invades others, which yield a higher profit. Through this incessant outflow and influx, or, briefly, through its distribution among the various spheres, which depends on how the rate of profit falls here and rises there, it creates such a ratio of supply to demand that the average profit in the various spheres of production becomes the same, and values are, therefore, converted into prices of production. Capital succeeds in this equalization, to a greater or lesser degree, depending on the extent of capitalist development in the given nation; i.e., on the extent the conditions in the country in question are adapted for the capitalist mode of production….

The incessant equilibration of constant divergences is accomplished so much more quickly, 1) the more mobile the capital, i.e., the more easily it can be shifted from one sphere and from one place to another, 2) the more quickly labour-power can be transferred from one sphere to another and from one production locality to another. The first condition implies complete freedom of trade within the society and the removal of all monopolies with the exception of the natural ones, those, that is, which naturally arise out of the capitalist mode of production (i.e.: the capitalist monopoly of capital, and the labour monopoly of labour-power. – ed.) …. – The second condition implies the abolition of all laws preventing the labourers from transferring from one sphere of production to another and from one local centre of production to another; indifference of the labourer to the nature of his labour; the greatest possible reduction of labour in all spheres of production to simple labour; the elimination of all vocational prejudices among labourers; and last but not least, a subjugation of the labourer to the capitalist mode of production.

(Marx, Capital, v. III, pp. 195-6.)[22]

Summary

Thus, under developed capitalism, there is sufficient mobility of the labour-force within the frontiers of the individual country for a tendency towards an equalization of the rate of surplus-value. Similarly, there is sufficient mobility of capital for a tendency towards an equalization of the rate of profit. This results in the fact that the exchange relationship between the commodities – their market price – no longer fluctuates around the value but around the price of production.

Now the question is, How is it internationally? Is the mobility of the labour-force sufficient for an equalization of the rate of surplus-value – i.e. of the rate of exploitation? Is the mobility of the capital between the countries sufficient for an equalization of the rate of profit and thus for the creation of prices of production? In short the question is, How does the capitalist world market function?

The World Market

As far as the rate of surplus-value is concerned, we feel absolutely convinced that no equalization has taken place internationally. The mobility of the labour-force between the countries has not been sufficient to produce anything at all like a tendency towards this. The development has been the opposite.

The industrial and parliamentary struggle, which was carried on by the working class in the imperialist countries at the end of the last century, led to an increasing wage level on the basis of the exploitation of the rest of the countries in the world. On the other hand this exploitation of the poor countries meant that they had no possibility of a similar development; on the contrary, during the twentieth century this situation resulted in an increasing disparity in wage levels between the developed and the underdeveloped countries, or, in other words, in a high rate of surplus-value in the poor countries and in a lower in the rich countries.

As far as the rate of profit is concerned, we believe that the international mobility of capital – particularly after the Second World War and the decolonization – has been sufficient to produce a tendency towards equalization, and thus sufficient for the determination of prices of production at an international level.

Thus the prerequisites[23] for the determination of the prices on the world market are:

1. Wages

Unequal payment of labour-power. Internationally, the class struggle has been fought on an unequal economic basis which has resulted in the wage level and consequently the rate of surplus-value varying enormously between the imperialist countries and the exploited countries.

2. Profit

Equal payment of the capital. The mobility of capital is sufficient to produce a tendency towards an international equalization of the rate of profit.

Unequal Exchange Between Countries

Let us see what these prerequisites lead to in Marx’s tables of prices of production:

We suppose two countries A and B. Firstly, we suppose that the rate of surplus-value and the rate of profit in the two countries are equal. This means that the mobility of the labour-force and the capital is sufficient for an equalization. (Table 3.3)

The organic composition of the production in the countries A and B is the same (c and v is 100 in both countries). This has been done to make “other things equal” – to eliminate the possibility that a higher organic composition should be the cause of any transfers of value. This means that in this case value and price of production coincide.

The equal organic composition in no way indicates that this is a question of a production of identical commodities, because then the wage increase in country A would mean that A’s commodities would be outstripped by country B’s lower prices. The characteristic feature of the trade between the imperialist countries and the exploited countries is namely that they exchange different commodities.

Finally, we suppose that the entire capital turns over at the same speed in both countries.

In Table 3.3 the rate of surplus-value and the rate of profit between the two countries have been equalized. Thus the exchange relationship between the two countries is equal.

In Table 3.4 a 50 per cent increase in wages has been introduced in country A, resulting in a lower rate of surplus-value – a lower degree of exploitation. This affects the exchange relationship between the two countries.

Table 3.3

Table 3.4

| Constant | Variable | Surplus- | Cost- | Value | Rate of | Average rate | Price of | |

| capital | capital | value | price | profit, % | of profit, % | production | ||

| c | v | s | c+v | c+v+s | s/C | P’ | (c+v) + P’xC | |

| Country A | 100 | 150 | 50 | 250 | 300 | 20 | 33.33 | 333.33 |

| Country B | 100 | 100 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 50 | 33.33 | 266.67 |

| 600 | 600.00 |

Equal quantities of labour-power are used in the two countries. It is only the price for the labour-power which is not the same and, therefore, the value of the production in the two countries is the same. The rate of surplus-value s’ is different in the two countries. But the rate of profit is the same. Because the price for labour-power is different, we get different prices of production even though there is the same quantity of human labour and the same quantities of value in the two countries.

Whereas the commodities in Table 3.3 were equally exchanged by 300 to 300, the wage increase of 50 per cent in Table 3.4 (which is moderate compared to the real differences) results in an unequal exchange: 333 1/3 and 266 2/3 respectively. Country B is balked of 300 – 66 2/3 = 33 1/3 as compared to equal exchange. And country A gains 33 1/3 – 300 = 33 1/3. In the case of a complete exchange of commodities between country A and country B, country A would gain 33 1/3 + 33 1/3 = 66 2/3. At the same time the wage increase in country A means that the overall average rate of profit falls from 50 per cent to 33 1/3 per cent.

In this way, value is transferred from countries with a low wage level to countries with a high wage level. Through the international commodity and capital markets, the rich imperialist countries benefit from trade with the poor countries by means of unequal exchange.

The colonial form of imperialism at the end of the nineteenth century gave rise both to higher wages in the developed countries and to extra profits. But the mobility of capital, which also was a result of imperialism, tended soon to equalize the differences in the rates of profit between the investments in the colonies and in the imperialist countries. The working classes of the imperialist countries succeeded through parliamentary and industrial struggles not only in maintaining but also in increasing the comparatively high wage level they had obtained compared to that of the proletariat in the exploited countries.

The efficient industrial struggle of the American and West European working classes and the simultaneous brutal suppression of the same political and industrial struggle in the Third World, has resulted in differences in wages of 10 to 20 times. The increasing international mobility of capital, particularly after the Second World War, has resulted in a tendency towards an equalization of the rate of profit. In general, capital invested in the Third World does not yield higher profits than capital invested in the imperialist countries. Therefore, the international differences in wages are felt in the prices. Commodities from the Third World are cheaper, and when the two groups of countries exchange commodities, value is transferred from the poor exploited countries to the rich imperialist countries.

On Exploitation Between Countries

In the last analysis, exploitation is an appropriation of other people’s labour. This is true whether it is one person’s exploitation of another person or one country’s exploitation of another.

The products of human labour are commodities or services and, therefore, the appropriation of human labour is the appropriation of these commodities and services. Consequently, all exploitation between countries is ultimately based on an unequal exchange of commodities and services.[24] This may either be reflected by a deficit in the balance of trade, which means that the imperialist country imports more commodities than it exports according to current world market prices, or the inequality may be found in the actual price formation. We believe the latter to be correct.

To simplify still further: one country can only gain something at the expense of another by taking more goods than it provides or by buying the goods it obtains too cheaply and selling those it provides at too high a price.[25]

(Unequal Exchange Revisited, p. 56)

During a long period and generally speaking, the imports of the Third World from the imperialist countries exceed their exports measured in world market prices. The countries of the Third World have to take loans continuously to cover this import surplus.[26] Thus the transfer of value from the Third World is not based on an export surplus to the rich countries measured in world market prices. The transfer of value takes place on the basis of an inequality of market prices as one of the price-determining elements contains an inequality – namely the wages.

The international mobility of capital and the consequential tendency towards an equalization of the rate of profit prevents the low wages in the poor countries from resulting in generally higher rates of profit of capitals invested in these countries. The national and international competition between capitalists means that the low wages do not result in higher profits but in lower prices. The low wages lead to low prices, and thus the consumers benefit from this, whether they are capitalists or wage-labourers. The consumers are first and foremost the population of the imperialist countries. Table 3.5 shows how the imperialist countries account for around 3/4 of the exports of the poor countries.

Table 3.5 Distribution of developing countries’ exports (per cent)

| Export to | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 |

| Industrial countries | 74.3 | 74.0 | 75.2 | 73.3 | 73.5 | 72.9 |

| Developing countries | 21.1 | 21.3 | 21.3 | 22.7 | 22.5 | 23.0 |

| Socialist countries | 4.6 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.1 |

| Total | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

(Source: International trade 1975/76 and 1977/78, GATT, Geneva 1976 and 1978.)

On Exploitation

Capitalist exploitation is not exclusively and in isolation connected to production or to the concrete relationship between capital and labour. Under developed capitalism, the exploitation must be seen in relation to the circulation of capital as a whole – i.e. both in relation to production and to the trade in commodities.

Under developed capitalism, value is transferred from undertakings of low productivity to undertakings of high productivity within one line of industry. Value is transferred from lines of industry with a low organic composition to lines with a high organic composition. Finance and trade capital can appropriate value without even being directly attached to the productive sphere. Value is transferred from countries with a low wage level to countries with a high wage level. All these transfers of value – conditions of exploitation – can only be understood, if the capitalist circulation is considered as a whole and not only on the basis of production. The basis of the surplus-value – the surplus-labour – is created in production, the appropriation and distribution of the surplus-value take place in the trade in commodities.

The fact that, technically, a person takes part in production as a wage-labourer does not necessarily mean that he or she is exploited and that he or she cannot exploit other people. Wage-labour is a sine qua non of capitalist exploitation but it is not enough. The exploitation depends on the actual ratio between the “necessary labour” (the wages) and the “surplus labour” (the surplus-value). Thus, if you can secure more value for your wages than you have created, you are not being exploited but you are exploiting.

In principle there is nothing new about this. In Grundrisse, pp. 434-43, Marx deals with the fact that through the determination of prices of production and a national average rate of profit, labourers could benefit from other labourers’ products being sold below their value to the extent that these products were part of their consumption. However, when he wrote Grundrisse in 1857-8, Marx did not regard this as something important. He writes:

As regards the other workers, the case is entirely the same; they gain from the depreciated commodity only in relation (1) as they consume it; (2) relative to the size of their wage, which is determined by necessary labour. If the depreciated commodity were, e.g. grain – one of the staffs of life – then first its producer, the farmer, and following him all other capitalists, would make the discovery that the worker’s necessary wage is no longer the necessary wage; but stands above its level; hence it is brought down….[27]

(Marx, Grundrisse, p. 439.)

Engels did not doubt the possibility of the British’ proletariat exploiting the colonial proletariat.

… the English proletariat is actually becoming more and more bourgeois, so that this most bourgeois of all nations is apparently aiming ultimately at the possession of a bourgeois aristocracy and a bourgeois proletariat alongside the bourgeoisie. For a nation which exploits the whole world this is of course to a certain extent justifiable.

(Engels to Marx, 7 October 1858, MESC, p. 110.)

And in a letter to Kautsky he wrote:

You ask me what the English workers think about colonial policy. Well, exactly the same as they think about politics in general: the same as the bourgeois think. There is no workers’ party here, you see, there are only Conservatives and Liberal-Radicals, and the workers gaily share the feast of England’s monopoly of the world market and the colonies.

Thus the fact that wages of a certain size can contain more value than the labour performed in order to get the wages is not something new. [28]

It is a question of quantity whether it applies in the case of a managing director with an annual salary of $100,000, or in the case of an assistant manager with a salary of $25,000 – or if it already applies to the skilled worker earning $15,000. It is a question of calculations, not of principles.

South Africa – A Concrete Example

A working class (labour aristocracy) may very well share in the exploitation of a proletariat. In order to illustrate this we shall look at a concrete example: the participation of the white working class in the exploitation of the black proletariat in South Africa. In his article “The White Working Class in South Africa” (New Left Review, No. 82, Dec. 1973), Robert Davis describes the basis of the high standard of living and racist ideology of this class, which can be explained by its participation in the economic exploitation of the black working class in South Africa.

Robert Davis writes:

For it is clear that a section of the labour-force will tend to become most fully tied to the bourgeoisie when it benefits from the extraction of surplus value, in other words when it participates in the exploitation of the majority of the working class. Tables II and III below represents an attempt to show that it is true of the white mining, industrial and construction workers in South Africa.

From Table II it is clear that the average white mining wage (and even the basic white rate) have been, for the whole period in question, consistently above what we have called the “average allowable wage with no surplus content”, very roughly an indication of the average wage each worker would receive if there were no exploitation.

Table II

Rough indication of white miners’ share in surplus produced in the mining sector (current prices)

| 1911 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | 1961 | 1970 | 1972 | |

| Total market value | ||||||||

| of sales (Rmillions) | 95,358 | 136,664 | 118,570 | 259,090 | 393,314 | 893,281 | 1,563,375 | 1,942,344 |

| Depreciation (C) | 28,030 | 35,685 | 35,470 | 71,834 | 142,726 | 341,216 | 615,046 | 632,739 |

| Wages (V) | 37,634 | 46,068 | 40,446 | 75,322 | 139,224 | 293,259 | 488,100 | 570,757 |

| Surplus (S) | 29,694 | 54,910 | 42,654 | 111,934 | 111,364 | 258,806 | 460,229 | 738,848 |

| Av. allowable annual | ||||||||

| wage with no surplus | ||||||||

| content (S+V/labor force) | R222 | R345 | R242 | R377 | R507 | R826 | R1,347 | R1,963 |

| Average white wage | R560 | R819 | R648 | R911 | R1,594 | R2,501 | R4,074 | R5,098 |

| Surplus content of | ||||||||

| white wage | R338 | R525 | R406 | R534 | R1,087 | R1,675 | R2,727 | R3,135 |

| Basic grade white rates | ||||||||

| (selected years) | R624* | R520* | R3,036 | |||||

| Average black wage | R62 | R64 | R59 | R69 | R110 | R159 | R235 | R302 |

| Rate of exploitation | ||||||||

| of black labour | ||||||||

| (S/total black wages %) | 181% | 331% | 232% | 365% | 240% | 278% | 316% | 415% |

* Lowest grade

Since the “average allowable wage with no surplus-content” represents an average free of employers’ exploitation, roughly speaking any group of workers who receives an average wage above this level trust either be contributing more labour power than the average, or else be receiving this higher wage at the expense of fellow workers, through some (work-place or national) political arrangement.

That the first possibility does not apply to white mineworkers is borne out by the following facts. In the gold mines the ratio of white wages to black wages in 1911 was 11.7:1, while by 1966 the gap had increased to 17.6:1. But between 1920 and 1965 the productivity of black gold miners rose from an annual rate of 222 tons of ore mined per man to 417 tons, per man – an increase of 188 per cent.[29] The productivity of the whole labour force had meanwhile increased from an annual rate of 39 fine oz. of gold per man to 51 oz. per man over the same period.[30] This represents an increase of 157 per cent. The black increase in productivity was therefore above the total average increase in productivity, and we therefore also conclude that the average white miner’s increase in productivity must have been rather less than that of his black colleague.

Table III

Rough indication of white manufacturing and construction worker’s share in surplus in those sectors (selected years, current prices

| 1960 | 1961 | 1965 | 1968 | 1969 | |

| Gross value of manufacturing | |||||

| and construction output | |||||

| (Rmillions) | 1,292 | 1,373 | 2,241 | 2,827 | 3,236 |

| Depreciation (aprox, at | |||||

| national average) (C) | 110 | 137 | 179 | 226 | 259 |

| Wages (V) | 652 | 695 | 1,228 | 1,613 | 1,675 |

| Surplus (S) | 530 | 541 | 834 | 988 | 1,302 |

| Allowable wage with | |||||

| no surplus content | |||||

| (S+V/labour force) | R1,483 | R1,555 | R1,854 | R1,862 | R2,002 |

| Awerage white wage | R1,870 | R1,901 | R2,727 | R2,955 | R3,095 |

| Surplus content of | |||||

| average white wage | R387 | R346 | R873 | R1,093 | R1,093 |

| Average Black wage | R389 | R451 | R582 | R643 | R576 |

| Rate of exploitation | |||||

| of black labour | |||||

| (S/total black %) | 241% | 213% | 171% | 141% | 195% |

In other words whilst black miners had increased their relative contribution of labour value, their relative income position had declined. So, indeed, did their real income: for the average black miner received less in real terms in 1966 (R71 at 1938 prices) than in 1911 (R72 at 1938 prices) [31] The reverse, of course, applies to the white miner. On productivity grounds, therefore, the differentials should have become smaller not larger. Increased productivity thus cannot account for the white miners higher than “allowable wage with no surplus content”.

Of course, the explanation for this state of affairs is political. Black wages are kept low by the laws against effective political and trade union organization, by the colour bar and by the migratory labour system – all official instruments of State policy. Black workers are therefore victims of a super-exploitation, which has tended to increase rather than to diminish (as the table shows). Since the average white wage is a significant amount above the “surplus free wage”, and since it is not based on higher productivity, the inescapable conclusion is that the white mine workers benefit from surplus value created by blacks; in other words they indirectly share in the exploitation of blacks, via their political support for the State and the economic privileges they receive from it in return. If we look at similar figures -for industry and construction, we see the same pattern repeated for fundamentally the same reasons.

In industry and construction, as well as in mining, the white worker has visibly benefited from political privilege, and if the same analysis were applied to other sectors of the economy, doubtless the same trend would appear. What can then be said, without fear of contradiction, is that since the white wage is high by virtue of political privilege, if this privilege were to disappear, the white wage would be reduced. This would be so in any type of society that replaced it: neo-colonial, independent (if such thing is possible) native capitalist, or socialist. In a socialist society, unless exceptionally high productivity were proven (not, as we have seen, true of the South African white worker), a worker’s income would tend to be close to the “allowable wage with no surplus content”. (this income would, of course, consist partly of collectively consumed items and there would be some contribution for new investments). The average white South African worker would therefore stand to lose at least one-third to two-thirds of his current income by the introduction of a socialist society, and must on economic grounds therefore be judged likely. to oppose either phase of the “two-stage” freedom struggle, as envisaged by classical Stalinist Strategy.

Global Inequality

Emmanuel has made a similar but global calculation:

In 1973, the average annual wage in the USA amounted to around 10,500 U.S. dollars. The population of the entire capitalist world at that time was about 2 billions six hundred millions, and there was a little over a billion economically active. To pay all these economically active people on an American scale would require close to 11,000 billions US $. However, the total national income of these countries in 1973 amounted to only $2,700 billion.

(The Socialist Project, p. 70) [32]

This means that even if the entire capitalist class was expropriated, that is if all profits were paid out as wages, and even if no money at all were put aside for investments and maintenance, each labourer could only get an average pay of $2,500, which is no more than a quarter of the average American wages.

In the same article Emmanuel continues:

This means that the United States can be the United States and Sweden can be Sweden only because others, that is the 2 billion inhabitants of the Third World, are not.

This also means that every material equalization from the top down is excluded. If by some miracle, a socialist and fraternal system, regardless of its type or model, were introduced tomorrow morning the world over, and if it wanted to integrate, to homogenize mankind by equalizing living standards, then to do this it would not only have to expropriate the capitalists of the entire world, but also dispossess large sections of the working class of the industrialized countries, of the amount of surplus value these sections appropriate today. It seems this is reason enough for these working classes not to desire this “socialist and fraternal” system and to express their opposition by either openly integrating into the existing system, as in the United States of America or the Federal Republic of Germany, or by advocating national paths to socialism, as in France or Italy.

(Ibid., p. 71.)

Thus, under developed capitalism – imperialism – the appropriation of other people’s abstract labour does not only take place in the relationship between capitalists and labourers. The high wage level of the population as a whole in the rich countries means that also the labourers are able to appropriate the surplus-value created in the poor countries so that the labourers are able to appropriate more value than they create themselves. This is a characteristic of the position of the working class in eastern Europe and North America today.

Notes

[1] See for example the Preface to A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy: “I examine the system of bourgeois economics in the following order: capital, landed property, wage labour; state, foreign trade, world market.” (MESW, p. 181.)

[2] Arghiri Emmanuel was born in Patras, Greece, in 1911. In 1942 he volunteered for the Greek Liberation Forces in the Middle East and was active in the April 1944 uprising against the Greek government-in-exile in Cairo. The uprising was crushed by British troops and Emmanuel was condemned to death by a Greek court-martial in Alexandria. He was granted amnesty at the end of 1945 and freed in March 1946. After the war he settled in Paris where he studied socialist planning. He received his doctorate in sociology from the Sorbonne. Until 1980 he was Director of Economic Studies at the University of Paris-VII.

The theory of unequal exchange was advanced by Arghiri Emmanuel at the end of the 1960s and put forward in his book L’echange inegal in 1969, published in English in 1972 by Monthly Review Press (Unequal Exchange, A Study of the Imperialist Trade). Emmanuel has supported and developed his theory in a number of articles and further investigations. (See Bibliography : B. Works By Arghiri Emmanuel).