The third and final section of the article addresses the connections between morality and politics, including the use of violence in a political context.

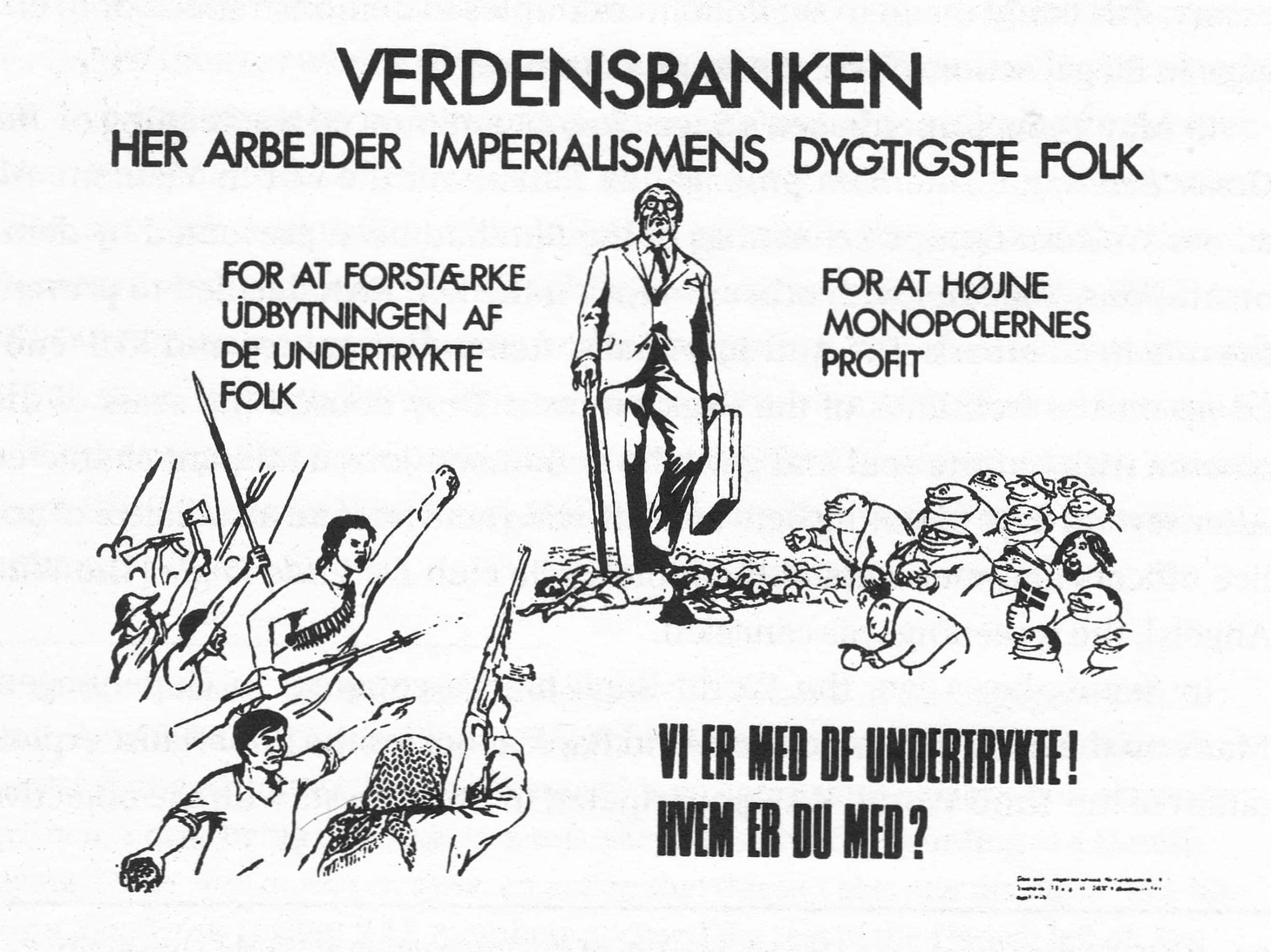

Violence has always been a central part of politics. This is an uncomfortable truth. Since World War II, there have been more than a hundred armed conflicts in the Third World causing the death of more than twenty million people. It is easy in contemporary Denmark to take a moral stand and reject violence as a political means, even if in reality most people are willing to use it, not least government officials. The boundaries between legitimate peacekeeping missions and criminal violence and terrorism depend largely on one’s political orientation. It is all about politics.

On the following pages we want to investigate both the claim that the ends justify the means and the claim that the ends never justify the means. We want to provide examples of the dilemmas you inevitably encounter as a political militant. We want to discuss the use of violence as a political means. And, finally, we want to shed some light on the relationship between liberation struggles and terrorism.

Do the Ends Justify the Means?

Among other things, PØK’s books about the Blekingegade Group caused a fiery debate about the group’s morals. With PØK’s “voice” as the main reference point, [51] most commentators agreed that the Blekingegade Group’s approach was “cynical.” We were portrayed as supporters of hijackings and of people using criminal means to achieve their goals. It was suggested that we blindly followed the motto of “the end justifying the means.” This is a statement often ascribed to Niccolò Machiavelli, author of The Prince, a little book written in the early sixteenth century. The Prince consists of numerous guidelines for how to govern. However, it is far from the first text to discuss the relationship between ends and means. In the tragedy Electra, the Greek dramatist Sophocles asked in 400 BC whether “the end excuses any evil,” while, in 10 BC, the Roman poet Ovid concluded in his lyrical collection Heroides that “the result justifies the deed.”

Balancing ends and means requires concrete reflections on what you find important and justified. If someone pursues ends that you do not consider important, it is easy to morally discredit the means. The accusation of someone following the principle of “the end justifying the means” comes easily. It is always convenient if you can accuse people you disagree with of immorality. On March 4, 2007, Politiken, one of Denmark’s biggest dailies, wrote, “Overall, the ‘voice’ admits that the end justified the means; that it was okay to do anything as long as it served the cause.” The Blekingegade Group was portrayed as a group of amoral villains that had turned against the apparent social consensus that the ends never justify the means.

Let us, for a moment, consider political reality rather than noble rhetoric. Is there really a consensus on the end never justifying the means? Here are three examples regarding the war in Iraq … [52]

- On December 5, 1996, shortly after being appointed U.S. secretary of state, Madeleine Albright was interviewed by Lesley Stahl for the TV program 60 Minutes:

Stahl: “We have heard that a half million children have died. I mean, that’s more children than died in Hiroshima. And – and you know, is the price worth it?”

Albright: “I think this is a very hard choice, but the price – we think the price is worth it.”

- On January 1, 2004, the Danish prime minister Anders Fogh-Rasmussen declared in his New Year’s television address to the nation: “I am certain that the liberation of the Iraqi people was and is worth all costs.”

- On February 20, 2005, Tøger Seidenfaden, the editor of Politiken, commented: “Seen with Western eyes, the noble end – democracy in the Middle East – justifies the harsh means.” This statement was made two years after the invasion, when the enormous number of victims was already known.

Apparently, when it comes to the war in Iraq, the consensus that the ends never justify the means is not valid.

If the motto of the end justifying the means implies that you can use any means you want (without any consideration for the consequences for others) in order to achieve any end you have decided to pursue, then the Blekingegade Group has never followed such a motto. At the same time, we have never followed the motto that the end never justifies the means either. After all, there is a third option – which, in fact, is much more realistic than the other two: not all ends justify all means, but, depending on the circumstances, some ends justify some means. This was the position that guided our actions. It is a position, of course, that implies challenges. One has to consider and balance three factors: ends, means, and circumstances. It is not always easy to draw the right conclusions.

We do not believe that Albright, Fogh, or Seidenfaden would argue that all means are justified once you have decided to pursue a certain goal (even if they obviously go a pretty long way: half a million dead children, seven hundred thousand casualties, and four million displaced Iraqis). The point, however, is that political actors have to be very clear about both their ends and their means. This requires a political discussion. Morality plays an important role in this discussion, but a reference to moral principles alone is not enough. In the eighteenth century, Immanuel Kant argued that the end alone can never justify the means, and that means need to be justifiable in and by themselves. This is an important reminder that the means we employ need to be carefully examined. But Kant’s argument does not rid us of the responsibility to go through a political discussion first.

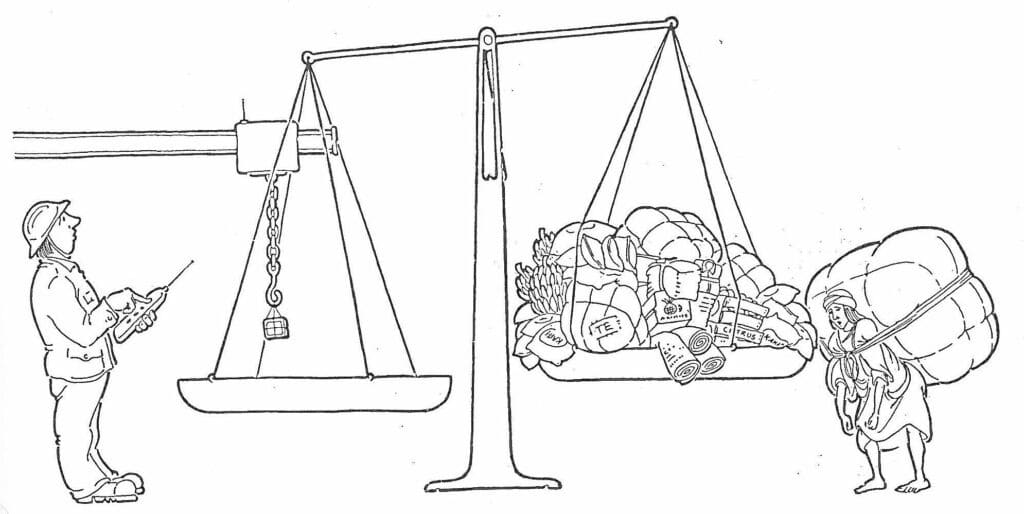

Most people find violence acceptable if the end is important enough and the situation urgent. For example, few people in Denmark would – politically or morally – question the use of violence in the context of the Danish resistance movement against the Nazis. Presumably, they would hold the same opinion even if the Nazis had won the war. By itself, the Danish resistance movement was not strong enough to defeat the Nazis. They were but a small wheel in the fight against them. Yet, the end of weakening Nazi Germany was enough to justify the use of violence. The resistance fighters sabotaged factories and railways in order to interfere with the production and delivery of goods important to the German war industry. Suspected collaborators were assassinated. But this does not mean that all means were acceptable. In recent years, some actions have also been criticized – for example, certain assassinations were based on weak evidence. Still, the overall opinion remains that under the given circumstances, the use of violence was justified.

It is hard to say where exactly the legitimate use of violence begins. In the case of the Danish resistance movement, the lines were drawn by the individual resistance groups and the individual resistance fighters. It was them who had to live with the decisions for the rest of their lives. This is the simple core question of each political dilemma: What do I do?

We also chose to be a small wheel in a big struggle. In this case, it was the global struggle against oppression and exploitation in colonies, settler states, and Third World dictatorships. We also have to live with this decision for the rest of our lives.

Machiavelli’s Use of “The End Justifying the Means”

Machiavelli’s book The Prince was published in 1532. It is a manual for the art of governing. It includes Machiavelli’s famous (and infamous) justifications of violence as a means to secure power. For example, he states that “a prince wishing to keep his state is very often forced to do evil.” [53] Essentially, the book is an honest description of how power functions, regardless of all ideological and moral considerations. One can read The Prince in various ways. To read it as a cynical manual for how to gain and defend power, is one option.

Machiavelli himself, however, suggests another reading: “It being my intention to write a thing which shall be useful to him who apprehends it, it appears to me more appropriate to follow up the real truth of the matter than the imagination of it.” [54]

Machiavelli was one of the Renaissance’s first secular thinkers. He wrote about separating religion (the dominant form of morality at the time) and politics. He refused to analyze political realities on the basis of religious dogma. He was, in contrast to many of his contemporaries, a realist, and he could not help but notice how far removed the theological idealizations were from the real and harsh world of politics. It is also important to remember the historical and political context in which The Prince was written. Machiavelli’s intention was not to aid royals in their exercise of power; it was to unite Italy.

Italy reached national independence in the fifteenth century based on a balance of power between five states: Naples, the Papal State, Florence, Milan, and Venice. Governance relied on strict rules, implemented by a tight-knit system of diplomatic representation. But from 1494 onward, Italian unity was attacked by France and Spain. Naples and Milan lost their independence and the other three states were under constant threat. In other words, the advice on ends and means that Machiavelli presented in The Prince was not based on general principles, but on a concrete historical situation, namely a nation being besieged. The same can hardly be argued in the case of the USA in 1996 (Albright) or of Denmark in 2004 (Fogh) and 2005 (Seidenfaden). The existence of neither state was threatened when the above statements were made. Arguably, in 1970, the situation was different for the Palestinians.

The 1970 PFLP Hijackings

When, in September 1970, PFLP commandos hijacked three civilian planes and ordered the pilots to fly to the Jordanian desert, the Palestinian nation was in a desperate situation. The U.S. secretary of state, William Rogers, had outlined a plan for the Middle East known as the Rogers Plan. The PFLP and most other Palestinian organizations as well as political observers considered the plan a blueprint for quelling the Palestinian resistance and eradicating any hope for a Palestinian state. This perception was strengthened by the U.S.-approved attacks of the Jordanian military on the Palestinian refugee camps, which had commenced a few months earlier. The PFLP hijackings have to be understood against this background. They were – if you allow us this figure of speech – an attempt to pull the emergency break in a situation that threatened the Palestinian struggle as a whole. The feeling was that something needed to be done to prevent the Rogers Plan from being implemented. It must also be noted that the hijackings ended with the airplanes being blown up, while all of the hostages remained unharmed.

It was not the first time that the PFLP had responded to attacks by taking hostages. When the Jordanian air force bombed Palestinian refugee camps for five days, from June 7 to 11, 1970, PFLP commandos occupied two of Amman’s main hotels and took the American, West German, and British guests hostage, demanding an end to the bombardments. At 5:00 AM on June 12, 1970, the PFLP’s general secretary, George Habash, gave a speech before the hostages at the Jordan Intercontinental Hotel. What follows is an excerpt:

Ladies and gentlemen! I feel that it is my duty to explain to you why we did what we did. Of course, from a liberal point of view of thinking, I feel sorry for what happened, and I am sorry that we caused you some trouble during the last two or three days. But leaving this aside, I hope that you will understand, or at least try to understand, why we did what we did. Maybe it will be difficult for you to understand our point of view. People living different circumstances think on different lines. They cannot think in the same manner and we, the Palestinian people, and the conditions we have been living for a good number of years, all these conditions have modeled our way of thinking. We cannot help it. You can understand our way of thinking when you know a very basic fact. We, the Palestinians for twenty-two years, for the last twenty-two years, have been living in camps and tents. We were driven out of our country, our houses, our homes and our lands, driven out like sheep and left here in refugee camps in very inhumane conditions. For twenty-two years our people have been waiting in order to restore their rights but nothing happened. Three years ago circumstances became favorable so that our people could carry arms to defend their cause and start to fight to restore their rights, to go back to their country and liberate their country. After twenty-two years of injustice, inhumanity, living in camps with nobody caring for us, we feel that we have the very full right to protect our revolution. We have all the right to protect our revolution. Our code of morals is our revolution. What saves our revolution, what helps our revolution, what protects our revolution is right, is very right and very honourable and very noble and very beautiful, because our revolution means justice, means having back our homes, having back our country, which is a very just and noble aim. You have to take this point into consideration. If you want to be, in one way or another, cooperative with us, try to understand our point of view. [55]

Habash’s words take us back to the original question of this chapter: “Does the end justify the means?” Did the twenty-two years of displacement and miserable living conditions in refugee camps – now exposed to bombardments – justify the occupation of hotels and the hijacking of airplanes? At this point, the question becomes concrete. It is no longer about abstract philosophical arguments, but about making a concrete political decision. Did these particular ends – the halting of bombardments of refugee camps and the creation of an independent Palestinian homeland – justify these particular means used under these particular circumstances? We thought they did. We tried to understand the PFLP’s perspective. But that doesn’t mean that there were no limits to the means that were justified, also for the PFLP. In both cases – the occupation of the hotels and the hijackings of the planes – the hostages remained unharmed.

The English philosopher Ted Honderich has approached this question differently, but he reaches the same conclusion: an occupied people has the right to resist and, if necessary, to use violence. He refers to the “principle of humanity” as a way to distinguish between a legitimate and an illegitimate use of violence. For him, the Palestinian situation is an example for what he considers a legitimate use of violence:

I have drawn a parallel between the resistance against the apartheid regime in South Africa and the resistance against the occupation of the Palestinian territories. When a people are oppressed and their homelands occupied, you cannot deny them the right to use violent means of resistance. … One lives a poor life when one cannot expect to live a long and healthy life, when one enjoys neither freedom nor civil rights, has neither respect nor self-respect, and possesses no possibility to create relationships with others and partake in cultural development. A politics that seeks to establish a good life corresponds to the principle of humanity. The Palestinians’ terrorist acts can be justified because they are directed against a power that denies them a good life. That’s why their struggle is legitimate, while, for example, Osama bin Laden’s is not. [56]

With respect to our approach, Ted Honderich looks at one of the factors we need to consider when deciding how to act politically: the justification of ends. He does not address the justification of means.

Struggling for Liberation Is Not Terrorism

The international actions of the PFLP and other Palestinian organizations from 1968 to 1972 made the entire world aware of the Palestinian situation. In the late 1960s, the Palestinians felt that no Western politicians or journalists even bothered to listen when they tried to tell them about their plight. As an old Palestinian told us, they felt like the “donkeys of the world.”

When KUF members put up posters in Copenhagen in 1969 in order to raise awareness about the situation of the Palestinians, the only statements of sympathy were unwished for because they came from the political right. To express support for the Palestinian struggle was considered anti-Jewish. Regarding the PLO’s international actions, for example, Noah Lucas has written that although this “earned it little sympathy in the world, it nevertheless succeeded in establishing the image of its cause as the quest of a victimized people for national self-determination, rather than a neglected refugee problem as it had hitherto been widely regarded.” [57]

The Palestinian demand for an independent state was practically ignored by the West, despite resolutions passed by the UN as early as 1947 (Resolution 181: Partition Plan for Palestine) and 1948 (Resolution 194: Right of Return for Refugees), both expressing a commitment to an independent Palestinian homeland. It is worth noting that the Western countries themselves had voted for these resolutions.

We found it both necessary and justified to support the Palestinian liberation struggle, especially in the context of commitments to and responsibility for a just global order. Either UN resolutions are binding for all, or one accepts the doctrine of “might makes right.” We considered the situation of the Palestinians so hopeless and miserable that “dirty” methods, such as hijacking planes, would at least give them a chance to be heard. We did not see the PFLP’s struggle as terrorism. The PFLP fought for a democratic and nonreligious state. Palestinians lived under the occupation of violent security forces.

The PFLP’s political leader was Abu Ali Mustafa. He worked openly in the West Bank, but was killed when an Israeli Apache helicopter fired two missiles into his office in Ramallah on August 27, 2001. The offices of Palestinian leaders in Ramallah are protected by the Oslo agreement, which Israel co-drafted and signed. Yet, the Israeli government decided to execute Abu Ali Mustafa without judicial process. According to the Israeli human rights organization B’Tselem, Israel has killed 232 Palestinians since the year 2000 in so-called “targeted killings,” that is, in assassinations executed by the state with no legal foundation.

These assassinations have also caused the death of 154 civilians. This has not led to any noteworthy international reactions. [58] Israel does not act like a constitutional state. In the occupied territories, there is no rule of democracy, only the rule of the fist.

The PFLP responded to the assassination of Abu Ali Mustafa on October 17, 2001, with the assassination of the Israeli minister of tourism, Re’havam Ze’evi. Ze’evi had probably been involved in the decision to kill Abu Ali. He was the leader of the National Union, an alliance of ultra-right nationalist parties, which, after the terror attack on the U.S. on September 11, 2001, had advocated ethnic cleansing by demanding that all Palestinians should be forced out of Israel and the occupied territories. The killing of Ze’evi was the reason for the PFLP being added to the list of terrorist organizations by the U.S. and the EU. So, when the PFLP uses violence against a state – even if it is an occupying power – this is condemned and called terrorism. When that same state uses violence against the people living under its occupation, it is called retaliation and self-defense. Sometimes, when Israel acts in a particularly brutal manner, there is some international criticism. But the only organizations that end up on the list of terrorist organizations are those formed by the people living under occupation.

A simple count of the victims that the conflict in the region has caused shows that the Israeli state has killed about five times as many people as Palestinian militants. According to B’Tselem, 4,789 Palestinians were killed by Israeli security forces or by Israeli civilians between September 29, 2000, and April 30, 2008. During the same period, 1,053 Israelis were killed by Palestinians. If one looks at the numbers for minors, there were eight times as many Palestinian victims as Israeli ones: 938 vs. 123. According to the same source, the majority of Palestinians killed were not selected targets but random civilians. [59] The international community might “regret” the violence of the Israeli state, while the violence of the Palestinians is condemned and criminalized. No one ever calls the support of the Israeli state criminal.

Violence as a Political Means

Politicians love to talk about democracy. They hate to talk about violence. This stands in complete contrast to both historical experience and political reality. Politicians all over the world implement and use growing apparatuses of violence. Also the Danish government uses violence increasingly in its foreign policy. The “peace dividend” promised after the fall of the Berlin Wall never came.

We have no romantic relationship to violence. We have seen the civil war in Lebanon with our own eyes. We have seen torched villages in Rhodesia. On television, we have seen bombs dropped from B-52s over Vietnamese cities, and we have seen children burned by napalm running from the jungle. However, we have no romantic relationship to nonviolence either. We did support the armed liberation struggles in many countries. [60]

It is not surprising that anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles turned violent. The violence of European colonialism and imperialism was extreme. Two lesser known examples are the following: the German colonists exterminated almost the entire population of South-West Africa (today’s Namibia) in 1904, [61] while in 1902, after taking over the colonial administration from the Spanish, the U.S. sent 125,000 troops to the Philippines to quell the liberation movement – the war cost the lives of half a million people.

The colonial attitude was summarized by the former British prime minister Lord Salisbury in his 1898 speech at Albert Hall: “You may roughly divide the nations of the world as the living and the dying … the living nations will gradually encroach on the territory of the dying …” [62]

The imperialism of the twentieth century has been equally brutal. The U.S. killed one million people during the war in Vietnam. France’s attempt to save the French settler regime in Algeria also cost one million people their lives.

It was against the backdrop of the Algerian struggle that Frantz Fanon, who was active in the Algerian liberation movement, wrote the book The Wretched of the Earth, in which he reflects both on his own situation and on the situation of Third World nations in general. He concludes that the people of the Third World – held down by violence, exploitation, and oppression – must rise and gain self-consciousness. He argued that liberation from the colonial system and independence could be achieved by violent resistance coordinated and led by liberation movements. In his preface to The Wretched of the Earth, Jean-Paul Sartre wrote:

Try to understand this at any rate: if violence began this very evening and if exploitation and oppression had never existed on the earth, perhaps the slogans of nonviolence might end the quarrel. But if the whole regime, even your nonviolent ideas, are conditioned by a thousand-year-old oppression, your passivity serves only to place you in the ranks of the oppressors. [63]

Our perspective was that systems of violence, often with the involvement of the U.S., stood in the way of democratic liberation and socialism. Take, for example, the CIA’s role in the coup against the democratically elected government of Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973, or the CIA’s endless meddling in the affairs of the countries of Central America. There was no hope for liberation without armed struggle in the Portuguese colonies of Mozambique and Angola, the racist regimes of Rhodesia and Southern Africa, or the right-wing dictatorships of Latin America.

Most liberation movements had originally been founded as legal political movements. South Africa’s ANC is one example. It advocated a nonviolent struggle until the late 1950s. Only after the Sharpeville massacre in 1960 [64] and the subsequent criminalization of the ANC did the organization turn to armed struggle.

In 1970, there was a wave of rebellions spanning the globe from Vietnam to Mexico and from South Africa to the U.S. We felt that this was the beginning of a revolutionary process we wanted to see grow. We were far from the only ones supporting armed struggle. In the early 1970s, the belief in armed struggle was much more commonplace within the left than it is today. This was also expressed in the publishing world. The back cover of the Danish edition of The Wretched of the Earth cites Klaus Rifbjerg’s review of the book in Politiken: “One of the most important texts – perhaps the most important – about the struggle in colonized countries is now available in Danish; it reveals an almost poetic anger and, at the same time, a compelling objectivity.”

In 1971, the renowned Danish publishing house Gyldendal released the anthology Den palæstinensiske befrielseskamp [The Palestinian Liberation Struggle] edited by Jens Nauntofte. It included interviews with Leila Khaled on hijackings and with George Habash on international politics. The book’s tone is very positive. It clearly speaks of a “liberation movement.” Militants who are called “terrorists” today, are referred to as fedayeens in the book, the Arab word for “partisans” or “those who sacrifice themselves.”

The sympathies of the left for the liberation struggles were met by criticism from the right. The boundary ran, unsurprisingly, right through the Social Democrats. Prime minister J.O. Krag and the minister for foreign affairs, Hækkerup, supported the U.S. war in Vietnam. Only when Anker Jørgensen criticized the 1972 Christmas carpet bombing of Hanoi did the party begin to change its position. [65] The U.S. dropped 7.6 million tons of bombs over Indochina. That is three times the amount of all bombs dropped by the Allies combined during World War II.

The bourgeois camp, represented by the Berlinske Tidende and Jyllandsposten newspapers, were certainly no principled opponents of the use of violence as a political means. Both defended the war of the U.S. in Vietnam until the very end. Jyllandsposten also expressed sympathies for Pinochet’s coup against Allende in Chile and deemed South Africa’s black population not ready for democracy. Erhard Jakobsen, the founder of Centrum-Demokraterne, was a staunch supporter of the apartheid regime and considered ANC members to be terrorists. [66] The ANC’s leader, of course, was Nelson Mandela – the celebration of Mandela as a great statesman is a more recent phenomenon.

What was our personal situation like in the late 1960s and early 1970s? We witnessed a global uprising on the one hand, and lived privileged lives in a Western country on the other. Our conclusion was that we had to act. We felt that there existed incredible injustice in the world and we wanted to contribute to a profound political and economic change. We also felt that we were in a position that allowed us to act, and that it would have been inexcusable if we didn’t.

We find it difficult to share the perspective of the “voice” in PØK’s book when it states that “one can never compare different forms of suffering.” To begin with, the quest for a better and more just world does not begin with a cost-benefit analysis. It begins with a simple statement: “Enough!” Reflections about what you can achieve, and at what price, come later. Secondly, if you want to act politically, you cannot escape such reflections. That was true for us, and it has been true for anyone who has ever been involved in political struggles. Why bother with global economic justice, social welfare, or health care if you do not want to alleviate suffering? How can you fight an occupying power, resist oppression, and rise up, if you’re not affected by certain forms of suffering in a particular way? We all are affected by certain forms of suffering in a particular way in our everyday lives. We care more about people who are close to us than about people we don’t know or who we count among our enemies. That is human. Everything else enters the realm of divinity.

We do not think that we gave ourselves “a moral free pass,” as PØK’s “voice” suggests. There were always lines we wouldn’t cross in our activities. Morality was always important, and we had innumerable discussions about the moral implications of our practice. This became very clear in relation to the Rausing kidnapping. All of us had problems with the idea. At the same time, we had been strongly affected by the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, the thousands of people killed, and the massacres of Sabra and Shatila. The struggle of the Palestinians was our struggle. They were our friends. We felt close to them and therefore shifted our moral boundaries – for a while. But that didn’t mean that anyone was issued a “moral free pass.” The plan, and the related anguish, took a hard toll on us all. A “moral free pass” would have meant to do nothing.

Global and National Contexts

Of course it was problematic to use violence in Denmark. But we did not see our practice as limited to the Danish context, we saw it in relation to a global struggle. We acted in a world that was divided between rich and poor countries; a world without global democracy in which the principle of “might makes right” determined international relations. Anti-imperialist movements with a democratic agenda and no backing by an armed liberation movement didn’t stand a chance against an imperialism armed to the teeth and ruthless in the execution of its power. From our perspective, transferring value from the rich countries to the poor, specifically if received by liberation movements, was justified.

Here is a concrete example: In 1947, the UN accepted – with Denmark’s vote – a partition plan for Palestine with the goal of establishing both an Israeli and a Palestinian state. Years went by and neither Denmark nor the UN security council did anything to enforce this resolution. While the Israelis had their state, the Palestinians were languishing in refugee camps. So what do you do as a democratic Danish citizen? Do you play by the democratic rules of your country or do you promote democratic rights internationally? What shall a democratic internationalist do when rich and powerful democracies lose all sight of democratic values in their foreign policies, and when this leads to people being robbed of the right to establish their own independent state? Does this make it justified to support their cause with illegal means? Those were the questions we were facing.

In this world of inequality, we lived and acted in a country in which there was no desire for revolutionary change. That’s why we did not send out communiqués explaining our actions, in contrast to organizations like the RAF, the Red Brigades, and others we have been associated with. In the Danish context, our activities were simply criminal. That was also the reason why we never felt that the legal system was treating us unjustly and why we never saw ourselves as political prisoners. In the context of the Danish state and legal system, we were criminals, pure and simple. We had answered the questions we were facing in a particular way, and we had to accept the consequences – even if the motivations for our criminal activities were rooted in an analysis of the global political system.

Of course there are problematic implications to acting undemocratically in a democratic country in order to promote democracy in an undemocratic world. Then again, there are also problematic implications for democratic countries to send their armies out into the world without any democratic principles. The war in Iraq is a case in point. This fundamental contradiction – between national democratic systems and undemocratic international relations – has not lost its significance in the age of globalization.

Conclusion

There have been many stories circulating about the Blekingegade Group for the past twenty years. They aren’t going away. Quite the contrary. The media always returns to the subject and law enforcement officers and politicians are happy to jump on the bandwagon. They have a particular motive: a hatred for the left of the 1970s. Apparent “investigations” are actually part of a political battle. People like Peter Øvig Knudsen and Jørn Moos also have personal motives of course. They want to sell books, work as “advisors” for film, TV, and theater, appear on talk shows, and give talks across the country. On the back cover of PØK’s two-volume history of the Blekingegade Group it says: “This is a documentation. The text is not the result of the author’s imagination; it is based on innumerable written and oral sources.” This is a truth with modifications.

We understand that the story of the Blekingegade Group is a good story. But it is not as spectacular and meaningful as some try to make it to be. The “Blekingegade Group” is on its way to becoming a label exploited by the media industry. It is turning into a money-making machine. But who owns the copyright to the story? We know that capitalism likes to lay claim on everything. However, this doesn’t mean that we have to play along.

In this article, we wanted to present our experiences and reflections in a condensed form. It is meant neither as an apology nor as a manifesto. It is, however, an attempt at telling our history in a political context. Instead of focusing on crime and drama, we would like to see a more nuanced debate about politics, ends, and means.

We also wanted to pass on the experiences of twenty years of work with KAK and M – KA, which can hopefully contribute to forming new political strategies.

The story of the Blekingegade Group is a story about political action as a reaction to the political action of others. It provides an example of how to connect national and international politics. It is a story of anger at injustice and a will to change the world. It is a story about doing something, since doing nothing was not an option for us. It is a story about political analysis and about reflections on what is true and what is not.

Global exploitation and inequality were the main causes of our political actions. As we know, global exploitation and inequality still exist. But so do the movements trying to end suffering and oppression. The struggle continues.

Notes

[51] In Peter Øvig Knudsen’s books about the Blekingegade Group, one of his sources is an anonymous former M – KA member, referred to as the “voice.” After the book’s publication, it was officially revealed that the voice belonged to Bo Weimann. – Ed.

[52] The examples are taken from Jørgen Bonde Jensen, Politiken og krigspolitikken – et læserbrev [Politics and War Politics: A Letter to the Editor] (Copenhagen: Babette, 2007).

[53] Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, translated by W.K. Marriott. Online at gutenberg.org

[54] Ibid.

[55] Habash’s speech was copied from the PFLP’s website (http://www.pflp.ps) a few years ago, where it is no longer accessible. [It is now online again on pflp.ps/english – Online ed.]

[56] “Nogle gange kan terror retfærdiggøres” [Sometimes Terror Can Be Justified], Interview with Ted Honderich by Mads Qvortrup, Information, December 27–28, 2008, 14-15. Online in Danish on Information.dk

[57] Noah Lucas, The Modern History of Israel (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1974), 437.

[58] Quoted from Berlingske Tidende, December 6, 2008.

[59] See B’Tselem – The Israeli Information Center for Human Rights in the Occupied Territories [The figures mentioned in the text does not seem to be available on btselem.org any more – Online Ed.]

[60] See also Torkil Lauesen, Det globale oprør [The Global Uprising] (Copenhagen: Autonomt forlag, 1994). On armed struggle and peace, see pages 117-31.

[61] Sven Lindqvist, Udryd de sataner (Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1992), 168; English edition: Exterminate All the Brutes (New York: The New Press, 1997).

[62] Lord Salisbury, “Speech at Albert Hall,” May 4, 1898, quoted from Andrew Roberts, “Salisbury, The Empire Builder Who Never Was”, History Today 49, no. 10, Online on historytoday.com

[63] Jean-Paul Sartre, Preface to The Wretched of the Earth (1961), quoted from MIA

[64] On March 21, 1960, sixty-nine people were killed when the South African police opened fire during a protest outside the police station of the township of Sharpeville, south of Johannesburg. – Ed.

[65] Jens Otto Krag, Per Hækkerup, and Anker Jørgensen were prominent members of Denmark’s Social Democrats (Socialdemokraterne). – Ed.

[66] Centrum-Demokraterne [Center Democrats] was a Danish center-right party that split off from the Social Democrats in 1973; the party dissolved in 2008. – Ed.