In this section we want to correct some of the wrong perceptions concerning the illegal practice of KAK and M – KA.

The Criminal Activities

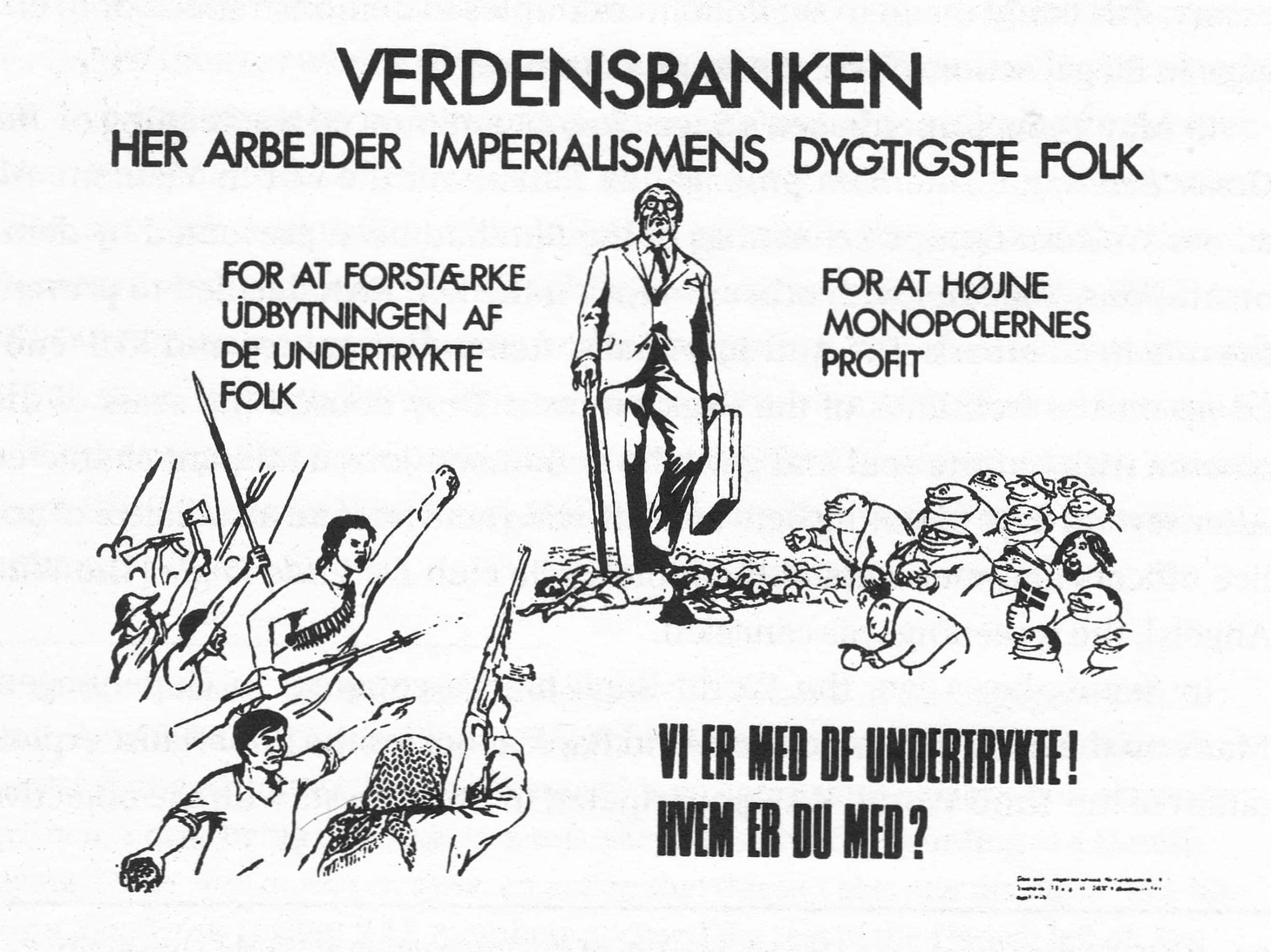

KAK was already involved in illegal activities in the late 1960s. This included painting slogans in support of the Vietnamese and Palestinian liberation struggles on bridges and commuter trains, actions directed against the sale of Israeli goods in Brugsen supermarkets as well as against the involvement of Denmark’s ØK company in teak logging in Thailand, and militant protests against the Green Berets screening in 1969 as well as against the World Bank congress in 1970. KAK also helped a group of Indonesian communists who were stranded in Eastern Europe after Suharto’s coup and the massacres of Communist Party members in 1967. They wanted to secretly return to Indonesia to help reestablish the Communist Party. KAK arranged for them to travel from Hungary to Denmark, provided them with fake papers, and arranged for the return journey to Indonesia.

Of course it was a big step to go from these activities to acquiring money for liberation movements by illegal means. But these activities functioned as a kind of bridge. They had shown which of the KAK members were ready for illegal action and they had trained these members in careful and secret planning.

KAK wanted to provide the liberation movements with more support than it had been able to so far. This was the main motivation for the first robberies. In the beginning, they were mainly experiments. After they proved successful, they became an increasingly important part of KAK’s practice.

PØK and other authors seem very excited about the idea of KAK members receiving training in Middle Eastern training camps. In their books, they return to this idea again and again. The problem is that no KAK members ever received training in Middle Eastern training camps. Yes, we have visited the PFLP many times. However, guerrilla tactics in the Middle East and criminal activities in Denmark have very little in common. In order to do what we did – in terms of planning, dealing with the security forces, and living a double life – one needed very specific knowledge about the conditions in Denmark. The PFLP couldn’t provide that. We had to learn all this ourselves.

As we have already mentioned, the motives of the KAK leadership for the illegal practice were not necessarily the same as those of the individuals involved. We believe that the leadership had two major motives: to provide financial support for the liberation movements and to train KAK members in illegal activities. For us – none of whom was part of the leadership at that time – there was only one motive, and that was to support the liberation movements as effectively as possible. That was the reason for agreeing to participate in these actions when we were asked to.

We always discussed options other than robberies. We thought about making money through investments – but no one in KAK (or M – KA, in later years) knew anything about investments. We had one member who knew about IT, but his knowledge did not allow for great moneymaking schemes. Jan Weimann has been called an IT expert in the press, but his former colleagues probably only got a good laugh out of that. The only time that IT knowledge was relevant for any of our actions was during the forgery of postal money orders in 1976 that gave us 1.4 million Danish crowns.

The conclusions we drew from the robberies we conducted from 1974 to 1976 were the following:

- Detailed and careful planning was necessary in order to remain in control. In particular, an escape route was needed that made chases impossible or, at least, very difficult.

- You could never expect rational reactions from the victims. For example, you could never count on threatening someone into handing you the money, you had to take the money yourself.

- Moments of surprise and fear were important in order to minimize resistance and therefore the use of violence.

We never thought about the psychological trauma we could cause. At least partly, this can be explained by the fact that psychological trauma was not discussed much at the time. Obviously, this has changed. There is no doubt that we underestimated the psychological effects that our actions had on others. Whether we would have acted differently if we had had a better understanding we don’t know, but we are certainly not proud of the psychological damage we have caused.

With every action we reached for a larger take. In a sense, this also increased the likelihood of something going wrong – both for the victims and for us. We tried to remain true to our principles, but we clearly made some wrong decisions along the way.

The organization that got the biggest support from us was the PFLP. The situation of the Palestinian people was very difficult. We also got to know PFLP members very well. We always acted based on our conscience, but the desperate situation of the Palestinians made us shift our limits. A number of events in the Middle East were very important for our practice: King Hussein’s attack on the Palestinian refugee camps in Jordan in 1970; the Lebanese civil war; the massacre at the Palestinian Tel Al Za’atar refugee camp in 1976, in which about six thousand Palestinians were killed; Israel’s heavy-handed repression of the Intifada; and the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982.

The Rausing Kidnapping Plan

In particular the massacres in the refugee camps Sabra and Shatila [45] made M – KA members believe that it was worth taking higher risks for both ourselves and the victims of our crimes. There was a strong sense that the PFLP now needed all the support it could get.

At first, the kidnapping of a German millionaire, a co-owner of the Würth company, was planned. The tip had come from the PFLP. We abandoned the plan because we felt that the victim was not well chosen. We were unsure about whether we could get a big enough ransom – or any ransom at all. Since we never came close to executing the plan, our emotional and moral limits were not tested.

Then we turned to a new plan, this time focusing on the Rausing family in Sweden. Jörn Rausing, a heir to the rich Tetra Pak company, was living in Lund, in the south of the country, not far from Copenhagen. We always had bad feelings about the plan. But time and time again, we overcame our reservations. We ground our teeth, thought of the situation the Palestinians were in, and continued. This is not meant as an excuse, it is a simple description of what happened.

The closer we got to the date set for the kidnapping, the more difficult it became to push our reservations aside. The date was postponed several times. The smallest obstacle was turned into a big deal – in hindsight, we simply couldn’t see the action through. There were a variety of reasons for this, whose importance probably differed from individual to individual.

First, there was the possibility of things going wrong; the plan was very complex and there were a number of risk factors.

Second, there was always the possibility that no ransom would be paid. We were quite certain that the Rausing family could and would meet our demands. But we could not be a hundred percent sure, which was bothering us. Besides, the whole thing went against our principle of taking money instead of threatening others into giving it to us.

Third, we couldn’t do this with only a limited degree of violence. Our plan was to drug Jörn Rausing and to take him to a hiding place in Norway. We tested the methods we wanted to use (both the drugs and the means of transport) on ourselves to get a better understanding of their consequences. We discussed this issue endlessly, never reaching any satisfying conclusions.

Fourth, we felt empathy with the victim. We had gotten to know Jörn Rausing quite well during the months we had been observing him. Had he been an unpleasant fellow, it would have probably been easier to execute the plan. However, he appeared to be a pretty average and quite likeable young man.

Fifth, there was a strong emotional dimension. In the end, we were simply appalled by the idea of kidnapping someone, and this feeling only became stronger with time. This was probably the most important reason.

In hindsight, it was idiotic to even consider this kind of crime. It would have been way too harsh on the victim and it went beyond our capacities. When the time came, we simply weren’t able to do it. Therefore, once the plan had been abandoned, we all concluded that we would never consider anything like this again. We decided that we should return to what we knew instead, which was robbery.

We thought that we could get away with the most spectacular coups, as long as the planning was right. However, it is difficult to be active for almost twenty years without making small mistakes. A single small mistake might not get you caught, but the mistakes add up and make you vulnerable. In retrospect, it wasn’t the actual robberies that made PET suspicious of us. It was the mistakes we had made in our communication with the PFLP and an increasing carelessness regarding security.

Living a double life had become normal for us. We got a lot of satisfaction out of being “good craftsmen” able to provide organizations with the money they needed. At the same time, the life we led included a lot of stress, bad conscience, and many sleepless nights. We will return to this in the last section of this article.

The Weapons in Blekingegade

Many weapons were stored at the Blekingegade apartment. Most of them came from burglaries at a Danish Army weapons depot in the water tower of Jægersborg and a Swedish Army weapons depot in Flen. This is an aspect of our activity that we regret for several reasons.

For our operations, we needed small weapons for the purpose of intimidation during robberies. So why did we amass hand grenades, land mines, antitank missiles, and explosives? As we explained at our trial, the weapons were meant to go to liberation movements. Our main plan was to smuggle them into Israel or the occupied West Bank. After the Israeli invasion of Lebanon and the massacres in the refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila, the PFLP expressed a strong need for weapons. We wanted to help.

To get weapons and to store them was not a big problem. The problem was to come up with a good plan to get them to Israel and the Palestinian territories. Unfortunately, we had not made such a plan before we got the weapons. Once we had them, it took us a long time to come up with ideas. In the end, all we were able to do was to set up a secret weapons cache in France where we were able to deposit at least some of the weapons and explosives for PFLP members to collect.

Before that, we had planned to smuggle weapons into Israel disguised as surfers. We found a car ferry that could take us from Greece to Israel. We also looked at different types of cars. Our choice fell on a Ford Grenada. It seemed most suitable for carrying concealed weapons. We also cut up a surfboard, put two antitank missiles inside, and glued the board back together. It was done so professionally that the police were still wondering what the surf-board was doing in the Blekingegade apartment after they had turned everything upside down several times. Eventually, Torkil asked his lawyer to tell the police about the contents. He was afraid that the missiles might explode if the board was handled carelessly.

Obviously, we were set on doing the trip ourselves. It was clearly easier for Europeans to smuggle weapons into Israel than for Palestinians. But we had our doubts. What if we were discovered? None of us wanted to spend time in an Israeli prison. So, we shelved the plan and it didn’t take long before we stopped considering it altogether. Instead, we contemplated getting rid of the weapons. But this wasn’t so easy either. We certainly didn’t want them to be discovered by anybody else. And how do you defuse an antitank missile?

PØK suggests that the weapons were meant for terrorist activities in Europe. That is incorrect. Just as incorrect as PØK’s claims about our contacts with the RAF, the Red Brigades, and Carlos the Jackal, or about our alleged collaboration with Wadi Haddad. But, once again, it adds to PØK’s tale if he can turn us into pawns of an “international terrorist network.”

Needless to say, it wasn’t smart to get all those weapons without a plan of how to transport them to their intended destination. It also meant that we ourselves gave rise to rumors about being involved in “civil war” and “terrorism” in Europe. However, as with all other aspects of our practice, the objective was simply to support Third World liberation movements. Not only did we reject military actions in Denmark and the rest of Western Europe morally and politically, but being involved in them could have also proven disastrous for our illegal practice, since it might have turned us into a prime target of the security forces.

In the end, the material support we were able to provide consisted of money, technical equipment, medicine, and clothes. We had the intention of providing weapons as well, but we failed to do so. That’s the reason why the weapons were found in Blekingegade. They caused us many logistical problems and exposed the Blekingegade tenants to an entirely unnecessary risk in the case of fire. This is something we regret.

The “Mild Spy Paragraph,” §108

Paragraph 108 of the Danish penal code became relevant during our trial because of the “Z-file” (Z for Zionism), often referred to as the “Jew file” in the press.

In 1981, the PFLP asked us to help identify people working for the Israeli intelligence service in Denmark. It was known that the Mossad used England and Denmark as informal headquarters of its European activities. In those countries, they were well received by the national intelligence services and guaranteed good working conditions. In France and Italy, for example, the relationship with the national intelligence services was much more complicated. This has also been confirmed by the former Mossad agent Victor Ostrovsky. [46] We ourselves had first-hand knowledge of Mossad agents trying to infiltrate Palestinian circles in Denmark.

The PFLP told us that they became increasingly suspicious about some of the many “left-wing tourists” from around the world coming to visit them in the Middle East. One example concerned the underground base in the Beirut refugee camp of Burj el-Barajineh. Visitors had inquired about the thickness of the walls. During the invasion of Lebanon in June 1982, the base was destroyed by so-called bunker busters. The PFLP felt that if they had a list of people possibly working for the Israelis, it would be easier to identify spies.

At first, we were hesitant. This kind of work was time-consuming and if we indeed got close to a Mossad agent it would put our own practice at risk. Yet, particularly in light of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon, we wanted to help. We decided to add another person to the illegal practice in order to handle the extra work that was required. This person was Bo Weimann, who, as a trained librarian, had the qualifications needed for the job. The Z-file became his main project.

We started with the assumption that anyone recruited as a Mossad agent in Denmark would have probably voiced pro-Israeli views at some point in the past. So we were looking for pro-Israeli (Zionist) sympathizers who suddenly stopped voicing their opinions in public.

The Z-file originally consisted of two parts. The first one listed companies, organizations, and periodicals that were pro-Israeli. The second one listed individuals who had voiced pro-Israeli opinions. The only concrete results of this work concerned the Wejra case. [47] We also identified one individual as a possible Mossad agent. In an attempt to produce more concrete results, we added a third part to the Z-file, listing everyone who had signed a petition in support of Israel in 1973. [48] The idea was to compare this list to the other two in order to find possible overlaps. A significant number of the individuals listed were – unsurprisingly – Jewish. That is why some journalists wrongly referred to the file as a “Jew file.”

We want to be very clear about one thing: We are not and have never been anti-Semites. We reject the Zionist project, whose objective has always been to create a purely Jewish state. The Palestinian people were displaced and their homelands occupied by Israel in two wars, in 1948-1949 and in 1967. We demand that the United Nations live up to their own resolutions guaranteeing the Palestinian people the right to a sovereign nation state. The United Nations have never enforced these resolutions. The Palestinian people have a legitimate right to resist the Israeli occupation, and we are on their side.

The Death of a Policeman during the Købmagergade Robbery

During our trial, two of us gave statements about the Købmagergade robbery and the shot that caused the death of a policeman. [49] We explained that the intention behind the shot was to puncture the police vehicle’s tires in order to prevent a chase. The prosecutors conceded that the shot was fired from the hip and unsighted. This was also confirmed by witness statements and the forensic evidence whose conclusion was that the policeman was hit by a stray pellet in the eye. The other pellets riddled the display window of a shoe store.

Bent Otken, the presiding judge, drew the following conclusion: “According to all the information we have, including the rapid development of events in Købmagergade, it cannot be assumed that the robbers had collectively agreed to fire at possible pursuers with the intent to kill.” [50] Therefore, Otken recommended that the jury not sentence us for intentional murder and we were acquitted on this count.

During the trial, it had not been possible to prove – or even make it appear probable – that this was a case of premeditated murder. If this had been the case, all of us could have been found guilty of murder. This was the conviction that the police were seeking.

We never reckoned that firing shots would be necessary during the Købmagergade robbery. We thought that the alarm from the cash-in-transit truck would go to the post office first, then from there to the police. According to our calculations, the probability of police arriving at the scene within less than two minutes was minimal. Unfortunately, we were wrong. During the trial, we came to understand that the alarm had gone directly from the truck to the police. Had we known this beforehand, our plan would have looked different. It was always mandatory for us to avoid direct confrontations with the security forces.

What was our plan in case a police patrol did arrive at the scene? In fact, two of them arrived. We met the first one in Løvstræde, right after turning out of the post office yard. We managed to pass it before two shots were fired at our van. One shattered the back window and got stuck in the driver’s seat. The second patrol car was waiting for us on Købmagergade. We pulled into the opposite direction and acted according to our plan, which was to stop and fire a warning shot against any vehicle trying to follow us, whether it was a police car, a post office truck, or a taxi. We carried a shotgun with us because it made a lot of noise. It was also loaded with big pellets that could puncture the tires of any possible pursuer. Unfortunately, one of those pellets hit the policeman.

Of course it implies a risk to bring a weapon to a robbery and to fire a warning shot. But none of us ever intended to take someone’s life. We deeply regret that it came to that. We cannot change what has happened, no matter how much we would want to.

PET and Us

We were under observation by PET for almost twenty years. We do not believe that this has ever happened without us being aware of it. Otherwise, it would have been impossible to gather at secret apartments several times a week for all this time without ever disclosing them.

The observations began in 1970, when Holger attracted attention in connection with the demonstrations against the World Bank congress. He enjoyed switching roles and began following the agents.

We developed a routine for how to behave when we noticed that we were observed. We acted as normally as possible, not letting anybody know that we were aware of the observation. Anything else would have seemed suspicious. We also developed methods to ensure that we were not observed when it would have compromised us.

PET agents were always easy to recognize. They were in their thirties and about six feet tall, they had nice clothes and usually were in good shape. There were always two people in a car. The cars were unassuming middle-class models in modest colors. Usually, three to four cars were working in shifts. The time patterns were very steady. We could often count on the observation ending on Friday at 4:00 pm and recommencing on Monday morning. Sometimes, things were done more professionally, but even then it hardly ever took more than a few minutes before you knew that someone was following you.

Niels and Holger were observed when they came home from the U.S. in 1979. It was basically revealed to them during a stopover in London. They were searched and questioned about their journey. When they asked for a reason for the interference, they were told, “We know very well what kind you are.”

Our homes were also searched. Sometimes, the agents didn’t return things to their proper place, or they were forced to leave in a hurry. We were convinced that our phones were tapped, and always used them carefully. When Torkil applied for a job at the Foreign Ministry, he was told that he could not be cleared. We knew that PET had an eye on us.

Our analysis was that PET knew about our contacts with the liberation movements, especially the PFLP, and that this was what made us interesting. They probably also knew that we were involved in illegal activities, but they didn’t know the details. When we were arrested in 1989, it became obvious that PET’s knowledge was limited. They arrested Peter Døllner who hadn’t been active in the group for many years, while they apparently didn’t know about the members who had joined later.

Notes

[45] In September 1982, at least eight hundred Palestinians were killed during a three-day period by Christian Phalangist militias in the Beirut refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila; the Israeli army, which controlled the area at the time, was accused of not interfering and even of providing logistical support. – Ed.

[46] Victor Ostrovsky and Claire Hoy, By Way of Deception: The Making and Unmaking of a Mossad Officer (Scottsdale: Wilshire Press, 1990); on Denmark, see pages 231–33 and 241.

[47] Wejra was a Danish weapons manufacturer that was accused in the 1980s of secret relations with Israel involving financial irregularities, illegal arms trade, and espionage. The company closed in 1990. – Ed.

[48] The petition expressed support for Israel during the Yom Kippur War. – Ed.

[49] Torkil Lauesen and Carsten Nielsen. See also “Solidarity Is Something You Can Hold in Your Hands” in this volume. – Ed. [Se the printet book, not online pt. – Online ed.]

[50] From the stenographic transcript.