Arrests (1989)

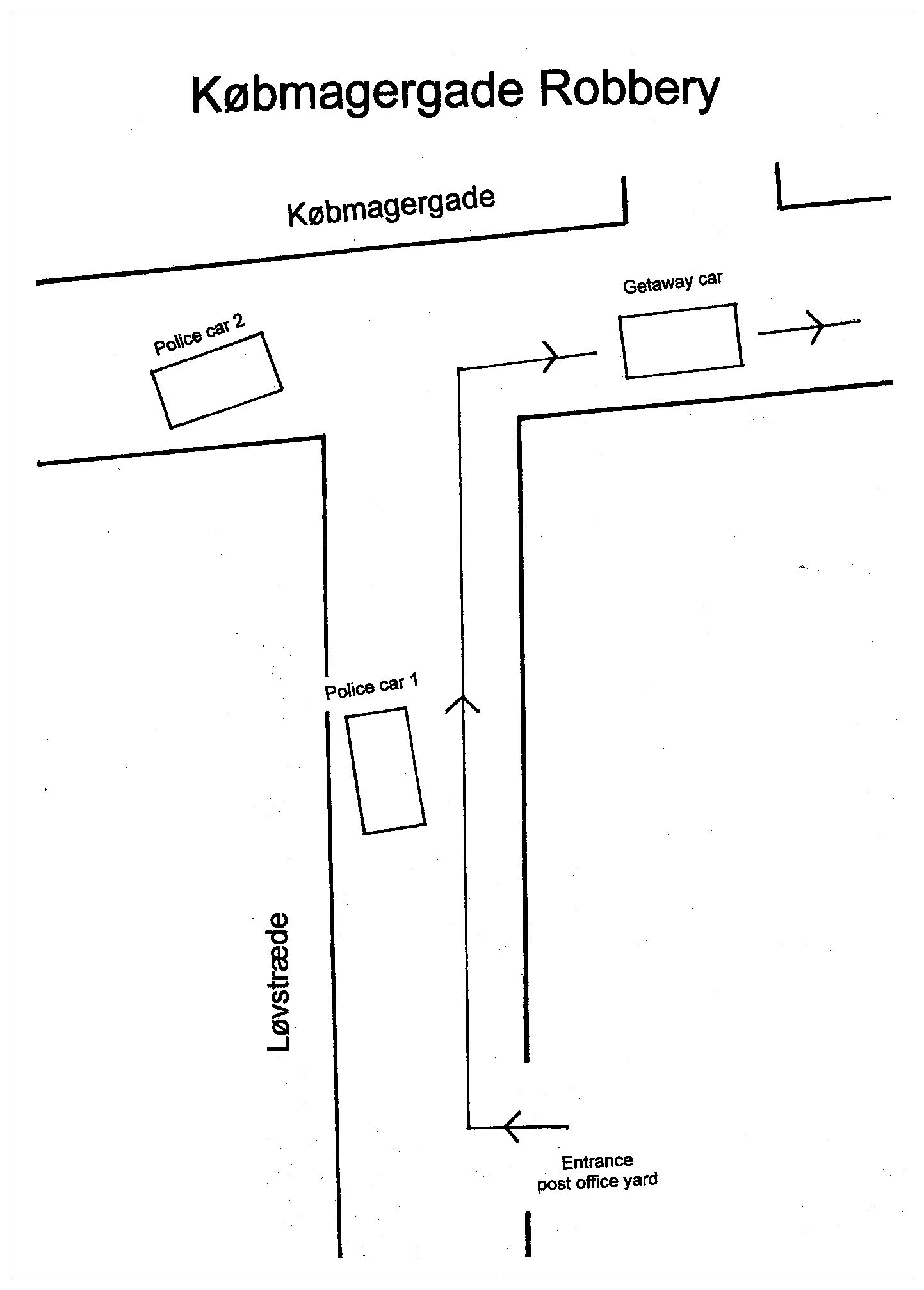

On April 13, 1989, five people are arrested in Copenhagen as suspects in a robbery that shook Denmark six months earlier. On November 3, 1988, five men had gotten away with over thirteen million crowns after holding up a cash-in-transit vehicle at the Købmagergade post office in central Copenhagen. The heist was Denmark’s most lucrative ever. It also left one person dead. With patrol cars unexpectedly arriving at the scene within less than two minutes, the robbers fired a shot from a sawed-off shotgun before making a close getaway. A pellet hit the twenty-two-year-old police officer Jesper Egtved Hansen in the eye, and he died in the hospital that same day.

Those arrested in April are Peter Døllner, Niels Jørgensen, Torkil Lauesen, Jan Weimann, and Niels Jørgensen’s former girlfriend Helena. [1] The four men have been under on-and-off surveillance by the Danish intelligence service Politiets Efterretningstjeneste (PET) for almost two decades and are known communist activists with close ties to Third World liberation movements, in particular the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, PFLP. It was a collaboration between PET and the Copenhagen police department that made them suspects in the Købmagergade case. While Helena is released the next day, the four men remain in custody, with the police issuing an arrest warrant for yet another suspect still at large, Carsten Nielsen.

With hard evidence missing, superintendent Jørn Moos, who leads the investigation, struggles to get permission from a Copenhagen judge to keep the suspects detained. Eventually, the judge grants Moos and his team three weeks to prepare a stronger case. If they fail, the men will go free.

Producing hard evidence remains difficult, however. Thorough searches of the suspects’ homes and interviews with family, friends, and coworkers remain fruitless. There is only one strong lead: identical sets of three keys found on Jørgensen, Lauesen, and Weimann. Officers test them on thousands of Copenhagen apartment doors, but with no results other than frightening unsuspecting tenants.

In the early morning hours of May 2, one day before the suspects’ release date, a police patrol car north of Copenhagen receives a call about a traffic accident nearby. A single male driver has run a rented Toyota Corolla off an empty country road into a power pole. He is badly injured and unresponsive. Several items in the car, such as wigs, lock-picks, and wads of foreign cash, arouse the cops’ suspicion. Alarm bells go off when the unconscious driver – who will lose his vision, his sense of smell, and his hearing in one ear as a result of the accident – is identified as Carsten Nielsen, the missing suspect in the Købmagergade case. Nielsen also carries a set of keys identical to the ones found on Jørgensen, Lauesen, and Weimann. In addition to this, the police find a bloodied telephone bill among a pile of papers on the Toyota’s backseat. It is made out to a firststory apartment at Blekingegade 2, a small and quiet street in Copenhagen’s Amager district, not far from the city center.

At 3:15 pm officers arrive at Blekingegade. A couple of minutes later they have opened the apartment with the suspects’ keys. This marks not only the beginning of Denmark’s most captivating twentieth-century crime saga but also provides one of the most puzzling and extraordinary chapters in the history of Europe’s militant anti-imperialist left of the 1970s and ’80s.

The Blekingegade apartment has obviously served as a center of sophisticated criminal activity. The police find crystal radio receivers, transmitters, and antennas; masks, false beards, and state-of-the-art replicas of police uniforms; numerous false documents and machines to produce them; extensive notes outlining the Købmagergade robbery and other unlawful activities; and – in a separate room, accessible only through a hidden door – the biggest illegal weapons cache ever found in Denmark. It includes pistols, rifles, hand grenades, explosives, land mines, machine guns, and thirty-four antitank missiles. Curiously, there is also a surfboard stored in the room.

The group that had access to the Blekingegade apartment is soon dubbed Blekingegadebanden, the “Blekingegade Gang,” or, less dramatically, Blekingegadegruppen, the “Blekingegade Group.” According to Torkil Lauesen, the name is the result of “particularly unimaginative journalism,” [2] but it is soon established among the public and used to identify the group to this day.

Beginnings: KAK (1963–1978)

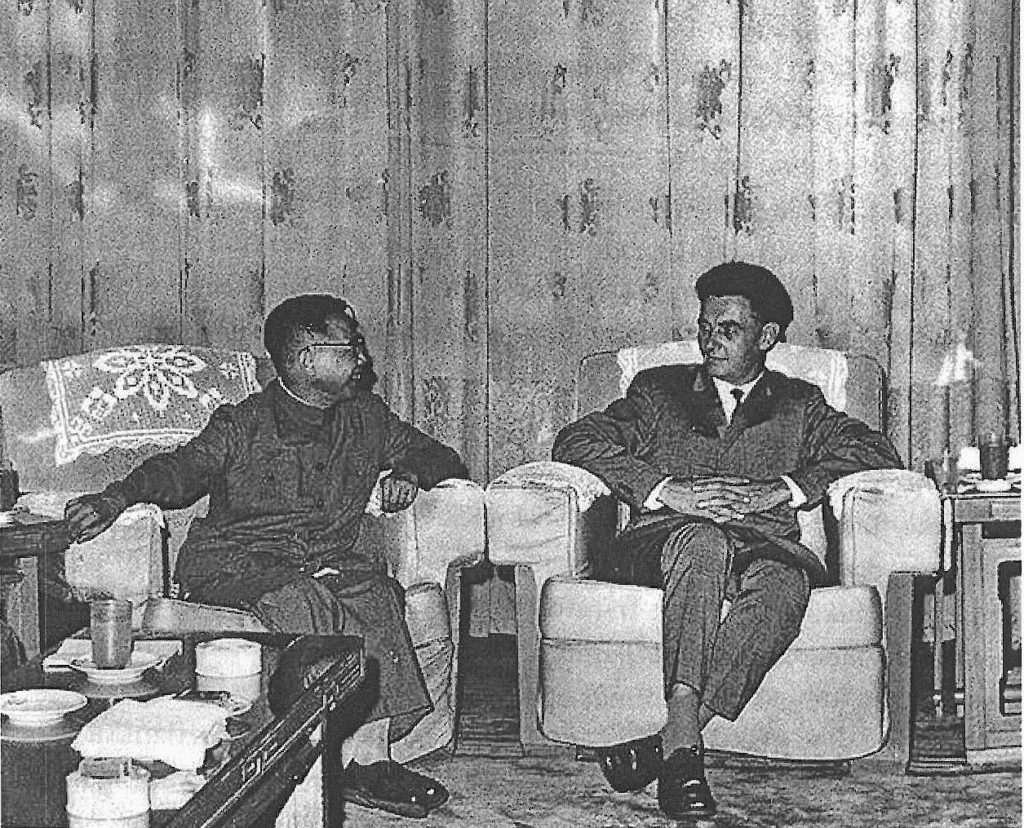

The origins of the Blekingegade Group date back to 1963, when a charismatic literary historian, Gotfred Appel, was excluded from the Moscow-loyal Communist Party of Denmark, DKP, due to his Maoist sympathies. A few months later, Appel and other disgruntled DKP members founded the first Maoist organization in Europe, namely the Kommunistisk Arbejdskreds [Communist Working Circle], KAK. KAK soon served as the official Danish sister organization of the Communist Party of China, CPC, and Appel regularly traveled to Beijing. KAK also founded the publishing house Futura, which collaborated closely with the Chinese embassy in Copenhagen, printing Maoist propaganda leaflets, the Chinese embassy’s newsletter, and Mao’s Little Red Book. KAK’s own newspaper, Orientering, was founded in December 1963; it was renamed Kommunistisk Orientering in September 1964.

During the following years, Appel developed his hallmark snylterstatsteori, the “parasite state theory.” In short, the theory claimed that the working class of the imperialist countries had become an ally of the ruling class due to its privileges in the context of the global capitalist system. Its objective interests were closer to those of Western capitalists than to those of the exploited and oppressed masses of the Third World. Therefore, the Western working class could no longer be considered a revolutionary subject. Only the masses of the Third World posed a threat to global capitalism by rebelling against the exploitation and oppression they were suffering. If their struggles were successful, the inevitable result would be a crisis of capitalism in the imperialist world, leading to the Western working class losing its privileges and being propelled back onto the revolutionary track.

The Vietnam War served as empirical evidence for Appel’s theory, and in February 1965 KAK organized one of the earliest European protests against the U.S. aggression. The fact that workers remained largely absent from the demonstration – despite strong mobilization efforts at some of Copenhagen’s biggest factories – seemed to confirm Appel’s analysis of a corrupted and complacent Danish working class. Yet he found numerous recruits among young radicals who were drawn to KAK by the Vietnam Committee (Vietnamkomité) that the organization had established, its militant stance, its uniqueness among the Danish left, and not least by Appel’s compelling personality.

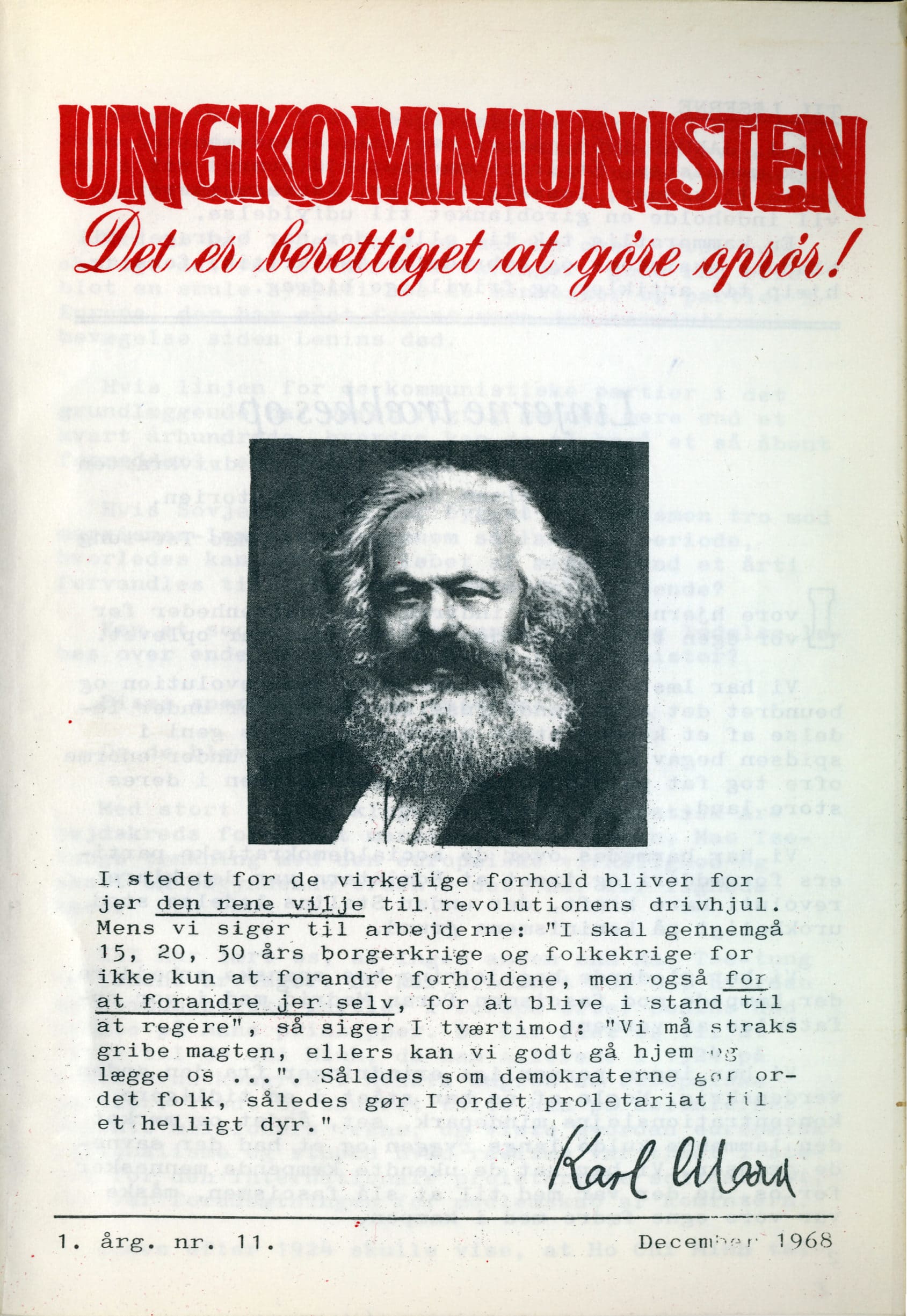

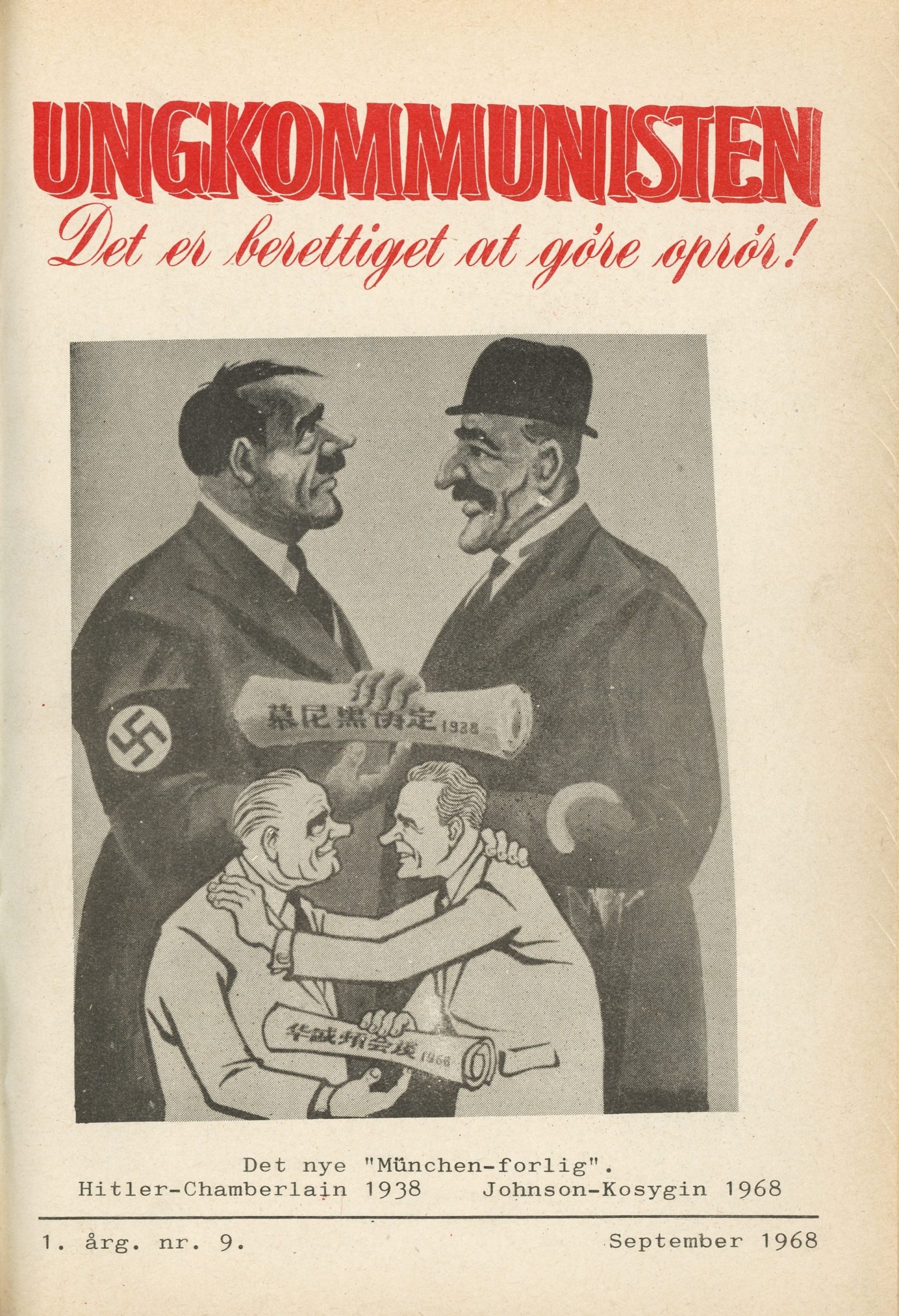

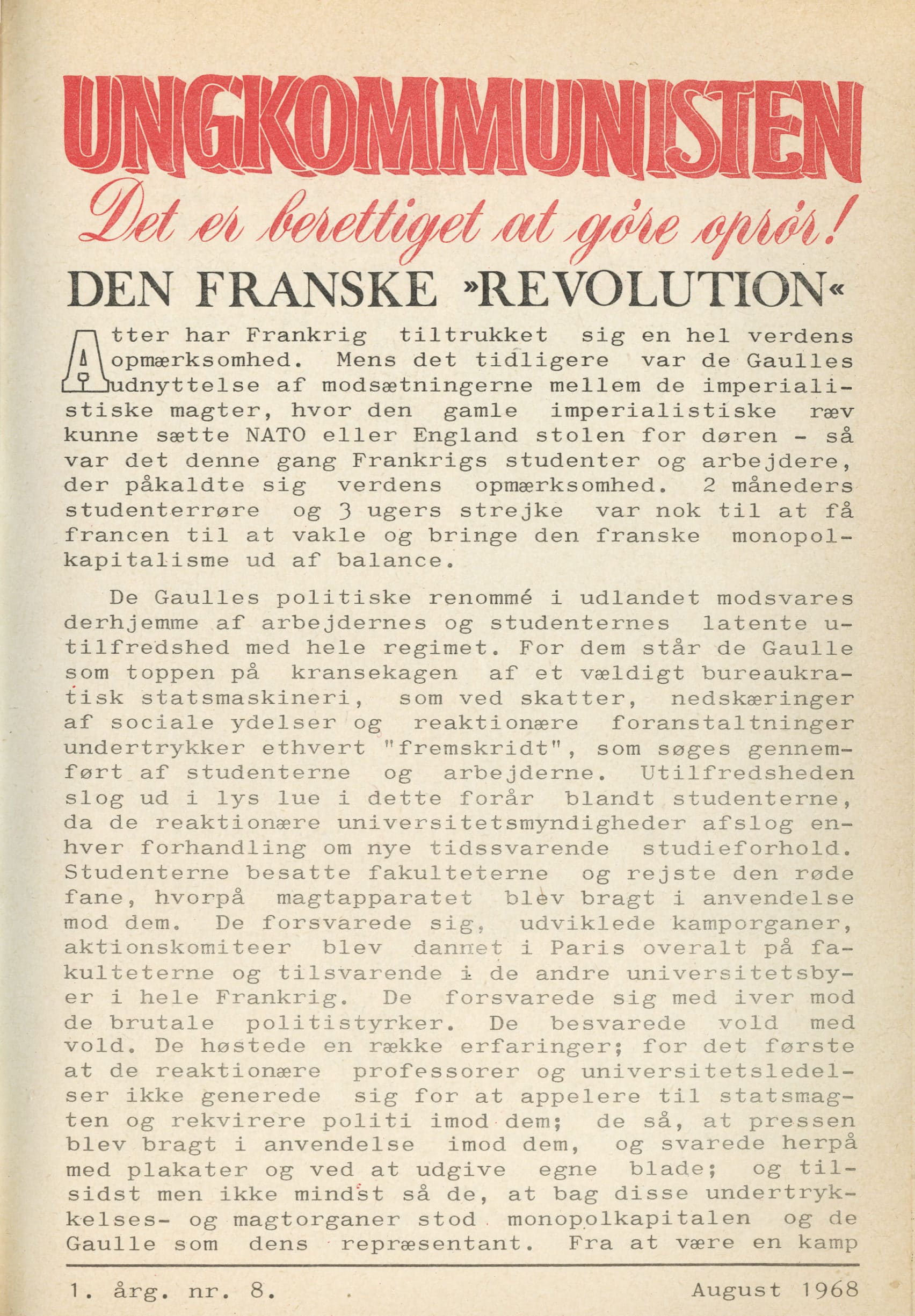

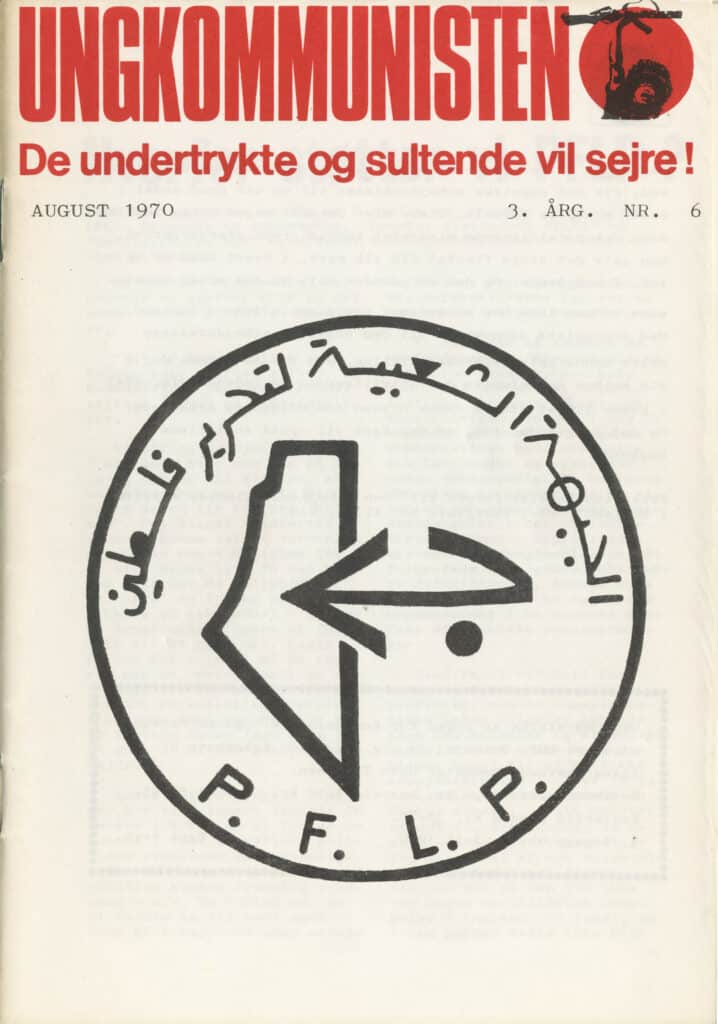

In 1968, KAK founded a youth chapter, the Kommunistisk Ungdomsforbund [Communist Youth League], KUF, which published its own journal, Ungkommunisten, and initiated a group called the Anti-imperialistisk Aktionskomité [Anti-imperialist Action Committee] in order to specifically attract sympathizers in the anti-imperialist milieu.

KUF played an important role for the history of KAK and soon counted some of the men among its members who, twenty years later, would be arrested as members of the Blekingegade Group: Peter Døllner, a young carpenter, and Jan Weimann, a passionate birdwatcher and excellent chess player who had just graduated from high school, joined in 1968. Both had grown up in the Copenhagen suburb of Gladsaxe. Another early KUF member from Gladsaxe was Jan Weimann’s high school friend Holger Jensen, an energetic and gregarious young man who became a driving force in both KUF and KAK. Niels Jørgensen, at the time only sixteen and still a high school student, joined in 1969. Torkil Lauesen, a medical student from Korsør, about a hundred kilometers west of Copenhagen, became a KUF member two years later.

In 1969, the relationship between KAK and the Chinese government turned sour. Gotfred Appel was not willing to make any compromises in his analysis of the European working class. When Chinese government officials hailed the European protest movements of the late 1960s, Appel criticized them relentlessly for overestimating the movements’ revolutionary potential and the participation of the working class. Eventually, this led to the end of KAK’s official ties to the CPC and the termination of the Futura publishing house’s contract with the Chinese embassy. From this point on, KAK was no longer aligned with any political party and pursued an independent anti-imperialist course, establishing relationships with various Third World liberation movements. It didn’t take long before Appel developed a particular interest in a Marxist-Leninist organization that had emerged in one of the world’s most volatile regions: the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, PFLP.

In 1970, Appel traveled to Jordan to meet with PFLP representatives. During the following years, several KUF members were sent to the Middle East for subsequent meetings. Members of the KUF and KAK rank and file

were also sent to numerous other regions in order to study the local political and economic conditions and exchange ideas with Third World liberation movements as well as anti-imperialist activists in the Western world. In Tanzania, the young Danes met representatives of FRELIMO, ZANU, and the MPLA; in Northern Ireland, Republican resistance fighters; and in Canada, members of the Liberation Support Movement, LSM.

To further strengthen the connections to African liberation movements, KAK founded the Tøj til Afrika [Clothes for Africa] project, TTA, in 1972. TTA collected clothes, tents, medicine, and money for African refugee camps administered by liberation movements. Soon, a number of TTA chapters were established around Denmark and the project provided a strong support network for KAK.

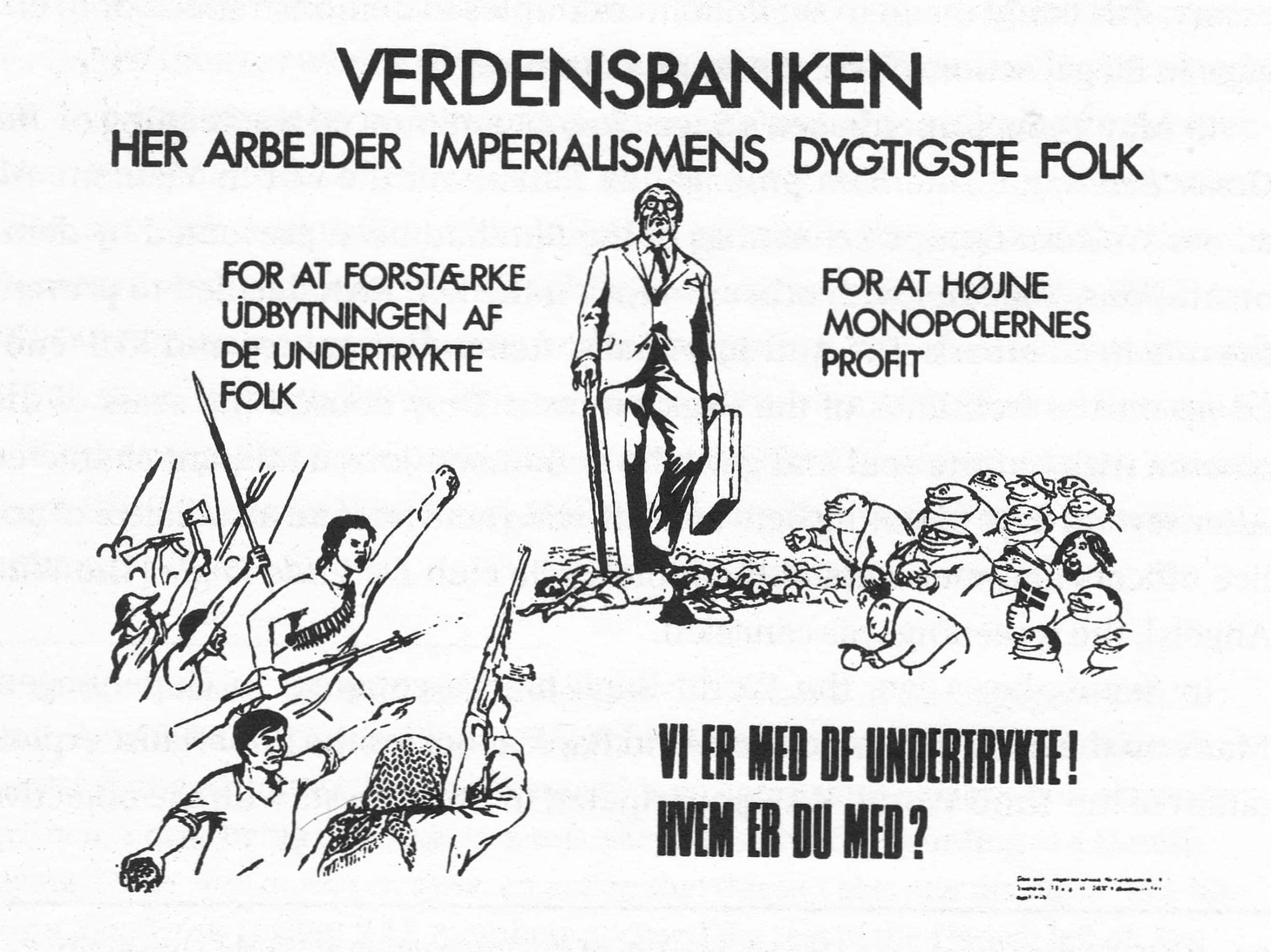

KAK itself kept a low profile in Denmark during the early 1970s. Following the protests against the World Bank congress in Copenhagen in 1970, during which KUF members were involved in heavy streetfighting, the organization had been targeted by security forces. Appel was furious and scolded the youngsters for their “lack of discipline” and “political immaturity,” since KAK’s strategy for the protests had focused on targeted militant actions rather than open confrontation with the police. As a result, KAK’s focus during the next few years was on theoretical study and the formation of a disciplined organization. Appel had no plans for KAK to become a mass movement. KAK never had more than twenty-five members and was mainly considered a training ground for elite revolutionaries ready to seize the revolutionary moment in the imperialist world when it came. Outward-directed work diminished steadily. Ungkommunisten had ceased publication in 1970, and Kommunistisk Orientering was on hiatus from 1970 to 1974. In 1975, KUF was officially dissolved. The remaining members were incorporated into KAK.

There was also another reason for KAK’s low profile during the early 1970s, however. It was the period when KAK developed what was later referred to as the “illegal practice.” In plain terms, this meant that robbery and fraud were used to supplement the material support for Third World liberation movements provided by Tøj til Afrika and other legal fundraising efforts. According to KAK’s analysis, providing material support for Third World liberation movements was the most effective way for Western militants to support world revolution.

Only a few selected KAK members were involved in the illegal practice. The rest of the membership was not informed. Essentially, this created an inner circle within the organization that consisted of people involved in illegal activities. It was this circle that marked the beginning of the Blekingegade Group. The men arrested in April 1989 all belonged to it from the beginning.

No KAK members were ever convicted for illegal actions committed during the 1970s. Yet they remain the main suspects for a number of unresolved crimes in the greater Copenhagen area, including the 1972 burglary at a Danish Army weapons depot (weapons from the depot were discovered at the Blekingegade apartment in 1989), the 1975 robbery of a cash-in-transit truck with a take of 500,000 crowns, the 1976 robbery of a post office with a take of 550,000 crowns, and a sophisticated 1976 postal money order scam with an unsurpassed take of 1.5 million crowns. All of the crimes shared features that would also characterize the ones that the Blekingegade Group was accused of in the 1980s: highly professional execution, a lot of loot, and no traces.

After discovering the Blekingegade apartment in 1989 and reconstructing the group’s history, there was much speculation about whether Gotfred Appel knew about the illegal activities of the 1970s, a fact that he sternly denied until his death in 1992. But former KAK and Blekingegade Group members speak of a tight, top-down organization in which nothing was done without the knowledge of the leadership, consisting throughout the 1970s of Appel, his partner Ulla Hauton, and the young Holger Jensen, with Jan Weimann joining in 1975.

The illegal practice – as well as all other KAK activities – came to a halt in 1977, when the organization hit a severe crisis. It started when accusations of male dominance were raised, in particular by Ulla Hauton. While Appel himself – judging from all accounts, unjustly – remained exempt from the criticism, many other male members were summoned to attend “criticism and self-criticism” sessions. Eventually, the sessions would include physical violence, with male members being expected to act as punishers in order to prove their willingness to change. A few months into what became known as the “anti-gender discrimination campaign,” most KAK members, including many women, felt that the campaign had gotten out of control. Their anger now turned toward Appel and Hauton. The latter in particular was accused of manipulating the female membership due to personal and internal leadership issues. Apparently, there had been particularly strong tensions between Hauton and Holger Jensen.

At a KAK meeting on May 4, 1978, Appel and Hauton were expelled from the organization by a majority vote of the rank and file. Some days later, Appel and Hauton expelled everybody else. After much back and forth, and Appel securing the legal rights to the name Kommunistisk Arbejdskreds, KAK split into three factions:

- Appel, Hauton, and a few allies continued to work under the name KAK and to publish Kommunistisk Orientering; two years later, the organization dissolved for good.

- Some former KAK members formed the Marxistisk Arbejdsgruppe [Marxist Working Group], MAG, which intended to reach a new form of political practice by analyzing KAK’s history. Members soon drifted away, however, and the group ceased to exist in 1980.

- Another group of former KAK members founded the Kommunistisk Arbejdsgruppe [Communist Working Group], KA, which soon became known as Manifest – Kommunistisk Arbejdsgruppe, M – KA, named after its journal, which appeared from October 1978 to December 1982. After that, Manifest mainly functioned as a press, publishing political books and pamphlets and printing materials for various liberation movements. Peter Døllner, Holger Jensen, Niels Jørgensen, Torkil Lauesen, and Jan Weimann all joined M-KA. None of them ever spoke to Hauton or Appel again.

In 1980, Holger Jensen died in a traffic accident when a truck hit the van he was sitting in outside a shopping center. Peter Døllner left M-KA in 1985. Jan Weimann, Niels Jørgensen, and Torkil Lauesen formed the backbone of the organization and of the Blekingegade Group until their arrests in 1989.

M – KA (1978-1989)

Ideologically, M – KA did not steer too far from KAK. It largely followed Appel’s parasite state theory. However, it also added new Marxist analyses of international relations to its theoretical framework, in particular the notion of “unequal exchange” developed by the Marxist economist Arghiri Emmanuel, who argued that the discrepancies in wealth between the industrialized nations and the Third World were primarily based on imbalances in wage levels and market prices. On various occasions, M – KA members traveled to meet with the Greek-born Emmanuel in Paris, where he lived and taught. Emmanuel also contributed a preface to the 1983 M – KA book Imperialismen idag: Det ulige bytte og mulighederne for socialisme i en delt verden [Imperialism Today: Unequal Exchange and the Possibilities for Socialism in a Divided World], which was published in English in 1986 as Unequal Exchange and the Prospects of Socialism.

The main difference between M – KA and KAK was organizational. M – KA was not focused on an individual leader, allowed more internal debate, and was more open to collaboration with other groups of the left. M – KA remained small, never extending to more than fifteen members. Material support for Third World liberation movements remained a priority. After the turmoil during the last months of KAK, the M – KA members managed to regain the PFLP leadership’s trust and reestablish contact with the other liberation movements they had collaborated with. The illegal practice continued. Once again, it was confined to an inner circle, without the rest of the membership being involved. Next to Døllner, Jørgensen, Lauesen, and Weimann, we know of three people who joined the inner circle during the 1980s. Karsten Møller Hansen, a Tøj til Afrika member from the chapter in Odense, was the first in 1982. He faded away only a few years later, but retained knowledge of most activities and contributed on occasion with small tasks. Also in 1982, Jan Weimann’s younger brother Bo joined the group, working in particular on the socalled “Z-file” (Z for Zionism), a collection of data intended to help the PFLP identify Israeli agents based in Denmark. Bo left the group in 1988. The Z-file proved highly controversial when it was discovered in the Blekingegade apartment in April 1989, and the media regularly referred to it as a “Jew file.” In 1987, Carsten Nielsen, a member of the Tøj til Afrika chapter in Århus, was the last one to be included in the Blekingegade Group.

Meanwhile, the core members’ personal lives had undergone significant changes. Jan Weimann was married, had two children, and worked as a respected IT technician at Regnecentralen, Denmark’s oldest IT company and the government’s main computer service provider. His brother Bo, married with a daughter, was one of his colleagues. The Weimann brothers’ families knew nothing about the illegal activities and their coworkers were in complete disbelief after the arrests, publicly doubting the police’s accusations. Torkil Lauesen had been trained as medical laboratory assistant, but only worked occasionally. In 1984, his wife Lisa gave birth to a daughter. Niels Jørgensen had already become a father in 1982, when he and his girlfriend Helena had a son. Jørgensen only worked part-time and changed his jobs regularly.

When the PFLP leadership was driven from Beirut as a result of the Israeli invasion of Lebanon in 1982, the M – KA members intensified their illegal activities. Much of the PFLP’s infrastructure had been destroyed and the organization was desperate for support, not least in the form of weapons. Consequently, in November 1982, the M – KA members robbed a Swedish Army weapons depot in Flen, about a hundred kilometers west of Stockholm. The loot included numerous boxes of explosives, over a hundred hand grenades and land mines, and the thirty-four antitank missiles later found in the Blekingegade apartment.

The Blekingegade Group has also been accused of several robberies that occurred in and around Copenhagen during the following years, but none of its members has ever been convicted for any of them. The alleged crimes include a post office robbery with a take of 768,000 Danish crowns in 1982, a cash-in-transit truck robbery with a record-breaking 8.3 million take in 1983 (two Palestinian men were arrested at Charles de Gaulle Airport in Paris with 6 million Danish crowns in cash three weeks later but were never extradited to Denmark), the 1.5 million crowns robbery of a post office in 1985, and a 5.5 million heist at the Daells shopping center in central Copenhagen just before Christmas in 1986. Meanwhile, the elaborate plan to kidnap Jörn Rausing, heir to one of Sweden’s wealthiest business families, was never executed. While material found in the Blekingegade apartment revealed that detailed preparations for the kidnapping had been made – including the transformation of a Norwegian summer house into a secret hideaway and demands for a ransom of twenty-five million U.S. Dollars – the plan was abandoned in the summer of 1985. The episode took a heavy toll on all members. Peter Døllner left the group as a result of it.

Preparations for the group’s final coup, the Købmagergade robbery, began in late 1987. According to the law enforcement agents working on the case, the group was one man short and the PFLP sent Marc Rudin, a Swiss national and longtime PFLP member, a few days before the robbery to fill the final spot.

The robbery itself went as planned. The Blekingegade Group members were on their way after exactly ninety-nine seconds, but a police patrol car had already positioned itself in the alley leading from the post office yard back to Købmagergade. Carsten Nielsen, who was driving the getaway van, managed to squeeze by, but the policemen fired a couple of shots at the vehicle. One bullet shattered the back window and got stuck in the driver’s seat.

When the van turned into Købmagergade, the group spotted another patrol car behind it. Nielsen stopped the van and one of the robbers stepped out in order to fire a shot from a sawed-off shotgun. Members of the group declared in court that the shot was meant to deter the police from chasing them and, ideally, to puncture the patrol car’s tires. The police investigation confirmed that the shot was unaimed and fired from the hip. Most of the pellets riddled the front of a shoe store. One, however, hit the twenty-two-year-old police officer Jesper Egtved Hansen in the eye, just as he had stepped out of the car. He was rushed to hospital, where he died the same day. The robbers managed to make their escape.

The death of a policeman caused unprecedented collaboration between Danish security forces, especially the PET and the Copenhagen police department, in the search for the culprits. The collaboration would eventually lead to the arrest and sentencing of the Blekingegade Group. Prior to the Købmagergade robbery, the interest in any such collaboration was limited from all sides. During the trial it was disclosed that the group’s members had been under on-and-off PET surveillance for almost two decades. The Copenhagen police department had even received tips after some of the robberies ascribed to the group, but those weren’t followed up on. At the same time, PET often withheld information because the agents seemed more interested in the group’s international contacts than in its domestic crimes.

The security forces’ combined efforts, however, were not the only reason for the group’s arrest. The members had also become increasingly negligent in security matters. Some of them have stated that if they had maintained their usual standards, there would have never been a trial. Apparently, ex-haustion had caught up with the Marxist revolutionaries who had turned into Denmark’s most successful criminals.

Prison (1989-1995)

Once the police had solid evidence against the men detained since April 13, 1989, more people with connections to M – KA and Tøj til Afrika were arrested. Karsten Møller Hansen on May 2, right after the discovery of the Blekingegade apartment, and Bo Weimann, Torkil Lauesen’s wife Lisa, and Møller Hansen’s former wife Anna [3] on August 10. Lisa and Anna were released a few weeks later. Neither was ever convicted of any crimes. Karsten Møller Hansen and Bo Weimann, however, joined Døllner, Jørgensen, Lauesen, Nielsen, and Jan Weimann in the dock.

The seven were originally indicted for numerous crimes, ranging from the illegal possession of firearms and the forgery of documents to murder and terrorism. The terrorism charge was dropped before the trial even started, however, which led to speculations about the Danish authorities giving in to political pressure and the fear of PFLP reprisals. Yet, this is dismissed as sensationalism by many, including the Blekingegade Group members. At the time, the Danish antiterrorist laws could simply not sustain a terrorism charge since they only covered acts targeting the Danish state. Today, things would be different. Since the former Danish prime minister and current secretary general of NATO, Anders Fogh Rasmussen, emerged as one of Europe’s staunchest supporters of the “War on Terror” in the early 2000s, Danish antiterrorist legislation has undergone dramatic changes.

The Blekingegade trial lasted eight months, from September 3, 1990, to May 2, 1991. The police and the prosecution committed many blunders, and the jury eventually acquitted the accused of most charges, most importantly murder. No individual shooter could be identified with respect to Egtved Hansen’s death, and no collective intention to kill established. The jury also decided against the application of a provision in the Danish legal code that allows the increase of maximum penalties by 50 percent if the circumstances of the crime are considered particularly heinous. In the end, Jørgensen, Lauesen, Nielsen, and Jan Weimann were declared guilty of the Købmagergade robbery, Bo Weimann of compiling the Z-file, and all of the accused, including Møller Hansen and Peter Døllner, of minor violations such as the illegal possession of firearms and the forgery of documents. Jørgensen, Lauesen, and Jan Weimann were sentenced to ten years in prison, Carsten Nielsen to eight, Bo Weimann to seven, Karsten Møller Hansen to three, and Peter Døllner to one year. Møller Hansen and Døllner were released on the spot (it is common in Denmark to be released after two thirds of the sentence). Bo Weimann and Carsten Nielsen were released in April 1994, Jørgensen, Lauesen, and Jan Weimann in December 1995. The last three had been especially active in prisoners’ rights issues during their time behind bars.

Marc Rudin was arrested on October 14, 1991, by a Turkish border patrol and accused of entering the country illegally from Syria. He was extradited to Denmark in October 1993, where he was sentenced to eight years in prison for his alleged participation in the Købmagergade robbery. He was deported to Switzerland in February 1997 and remains barred from entering Denmark.

Aftermath

The Blekingegade Group’s story has been captivating Denmark for over twenty years. Attention has been particularly strong in recent years, mainly due to the 2007 release of a two-volume, eight-hundred-page history of the group titled Blekingegadebanden and authored by the acclaimed journalist Peter Øvig Knudsen. The book sold 350,000 copies in Denmark, which made it one of the country’s most successful nonfiction books ever. It has been translated into Swedish, Norwegian, and (in an abridged version) German. In 2008, a one-volume “luxury edition” was published, including numer-ous original documents from the police files. Bo Weimann was the only former Blekingegade Group member who agreed to be interviewed by Øvig Knudsen. He was also the main protagonist of a 2009 documentary film titled Blekingegadebanden. Meanwhile, the journalists Anders-Peter Mathiasen and Jeppe Facius published two books in collaboration with the chief investigator in the Blekingegade case, Jørn Moos: Blekingegadebetjenten – kriminalinspektør Jørn Moos fortæller [The Blekingegade Cop: Superintendent Jørn Moos Tells His Story] (2007) collects stories from Moos’s professional life, while Politiets hemmeligheder: Kriminalinspektør Jørn Moos genåbner Blekingegadesagen [Secrets of the Police: Superintendent Jørn Moos Reopens the Blekingegade Case] (2009) focuses on the complicated relationship between the Danish police and PET – it also provided the basis for the 2010 documentary film Blekingegade – sagen genoptaget [Blekingegade: The Case Reopened]. In January 2009, the play Blekingegade, written by Claus Flygare, opened at Husets Teater in Copenhagen, and in the winter of 2009-2010, the TV series Blekingegade – quite openly blending fact and fiction – aired on public Danish television.

About This Book

This book was largely motivated by the portrayal of the Blekingegade Group in mainstream media.

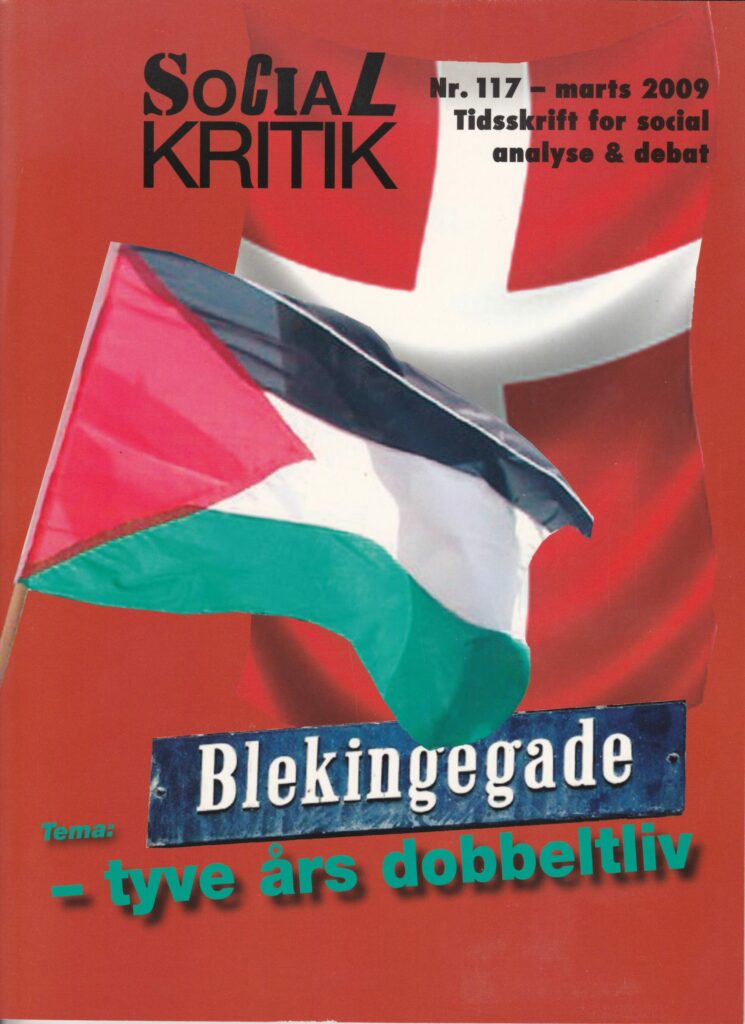

In 2008, Niels Jørgensen, Torkil Lauesen, and Jan Weimann wrote an article titled “Det handler om politik” (translated in this volume as “It Is All About Politics”) in response to Øvig Knudsen’s book. The article was published in a Blekingegade Group special of the Danish left-wing periodical Social Kritik in March 2009. A slightly revised version appeared on the website www.snylterstaten.dk shortly after. “It Is All About Politics” tells the story of the Blekingegade Group from the perspective of its longest-standing members and constitutes the first part of this book. The version included here has been adapted to an international audience in collaboration with Torkil Lauesen and Jan Weimann; Niels Jørgensen died in September 2008. Passages requiring a profound knowledge of Danish society, politics, and law, or a reading of Øvig Knudsen’s work have been omitted.

The book’s second part consists of an extended interview with Torkil Lauesen and Jan Weimann, conducted in the spring of 2013. The interview includes additional information on the group’s history and discussions about current socialist and internationalist politics.

The book’s third part brings together several historical documents: a 1966 essay by Gotfred Appel titled “Socialism and the Bourgeois Way of Life,” KAK and M – KA self-presentations, and the chapter “What Can Communists in the Imperialist Countries Do?” from the M – KA book Unequal Exchange and the Prospects of Socialism.

The preface by Klaus Viehmann was originally written for the German edition, published by Unrast Verlag. All translations were done by the editor.

The intention behind this book is to contribute to left-wing movement history. The activities of the Blekingegade Group constitute one of the most unique chapters of radical socialist and anti-imperialist politics in Europe during the 1970s and 1980s. While a number of secondary sources have been published, most notably Øvig Knudsen’s study, none of the material has been made available in English. Furthermore, even in the Nordic languages a book featuring the recollections and reflections of the group’s key members has been missing. As an editor, I have seen my role as providing a space in which these recollections and reflections can be expressed. Their political evaluation is left to the reader.

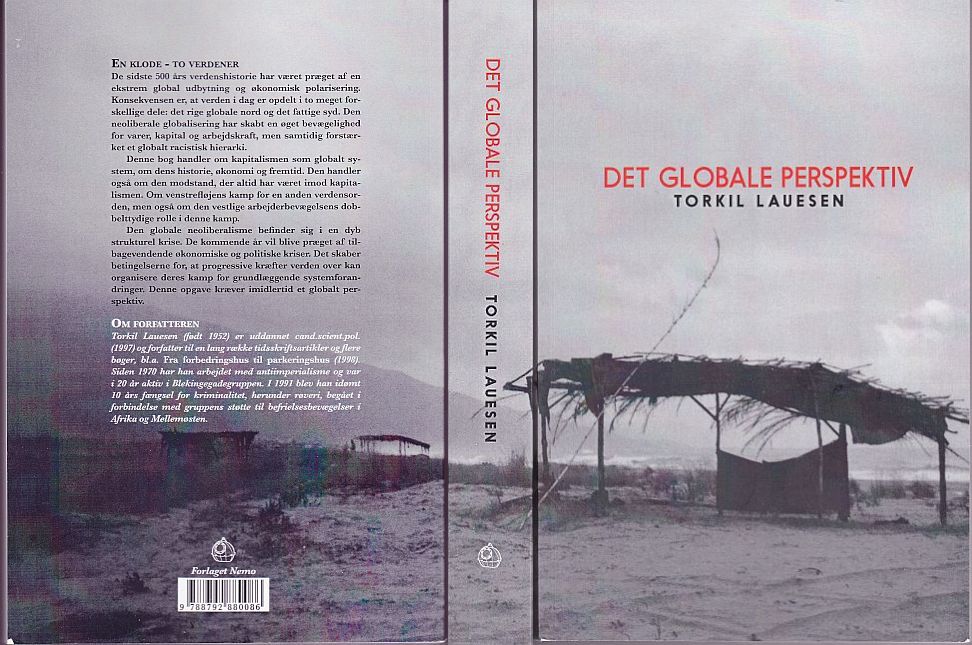

I would like to thank Poul Mikael Allarp, a former KAK and MAG member who maintains the website www.snylterstaten.dk, and Torkil Lauesen and Jan Weimann for their collaboration during this project and for providing valuable material from KAK’s and M – KA’s history. Today, Torkil Lauesen works for the city of Copenhagen in a neighborhood renewal project and regularly contributes to left-wing journals. On the basis of his prison experiences, he has also written the book Fra forbedringshus til parkeringshus – magt og modmagt i Vridsløselille Statsfængsel [From Rehabilitation to Warehousing: Power and Counterpower in the Vridsløselille State Prison] (1998) and the prisoners’ manual Att leva i fängelse – en överlevnadshandbok för fånger [Life in Prison: A Survival Manual for Prisoners] (2000). Jan Weimann works at a Copenhagen job center which tries to find work for the unemployed. He still enjoys watching birds and checkmating the king.