About the text:

From: On Colonies, Industrial Monopoly and Working Class Movement, Futura, 1972, 57 p., p. 35-37.

(Extract)

… Among the material sent you will also find some of the resolutions of the General Council of November 30 on the Irish amnesty, resolutions that you know about and that were written by me; likewise an Irish pamphlet on the treatment of the Fenian [12] convicts.

I had intended to introduce additional resolutions on the necessary transformation of the present Union (i.e., enslavement of Ireland) into a free and equal federation with Great Britain. For the time being, further progress in this matter, as far as public resolutions go, has been suspended because of my enforced absence from the General Council. No other member of it has sufficient knowledge of Irish affairs and adequate prestige with its English members to be able to replace me here.

Meanwhile time has not been spent idly and I ask you to pay particular attention to the following:

After occupying myself with the Irish question for many years I have come to the conclusion that the decisive blow against the English ruling classes (and it will be decisive for the workers’ movement all over the world) cannot be delivered in England but only in Ireland.

On January 1, 1870, the General Council issued a confidential circular drawn up by me in French (for the reaction upon England only the French, not the German, papers are important) on the relation of the Irish national struggle to the emancipation of the working class, and therefore on the attitude which the International Association should take in regard to the Irish question.

I shall give you here only quite briefly the decisive points.

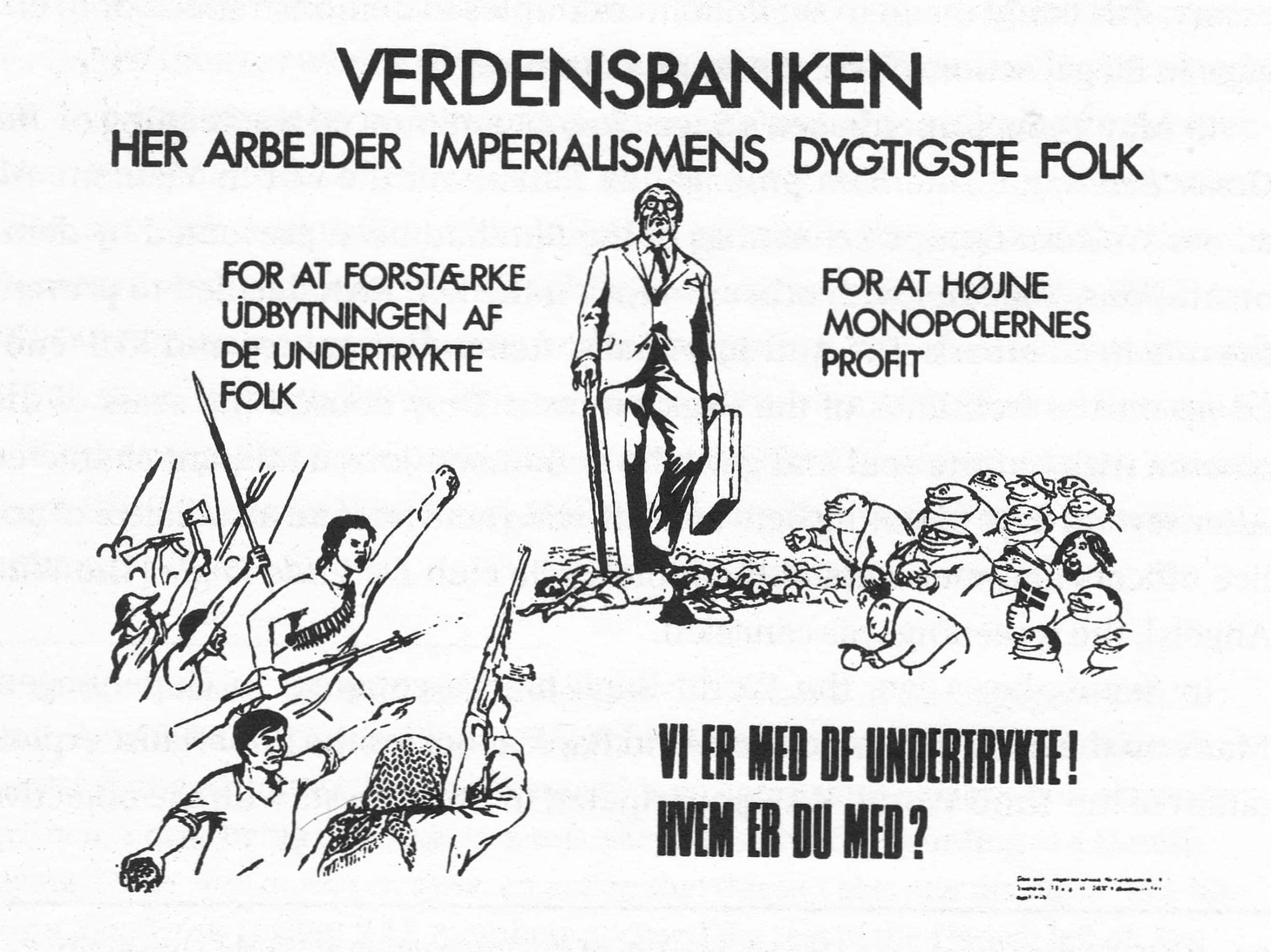

Ireland is the bulwark of the English landed aristocracy. The exploitation of that country is not only one of the main sources of this aristocracy’s material welfare; it is its greatest moral strength. It, in fact, represents the domination of England over Ireland. Ireland is therefore the great means by which the English aristocracy maintains its domination in England itself.

If, on the other hand, the English army and police were to withdraw from Ireland tomorrow, you would at once have an agrarian revolution there. But the overthrow of the English aristocracy in Ireland involves as a necessary consequence its overthrow in England. And this would fulfil the preliminary condition for the proletarian revolution in England. The destruction of the English landed aristocracy in Ireland is an infinitely easier operation than in England itself, because in Ireland the land question has hitherto been the exclusive form of the social question, because it is a question of existence, of life and death, for the immense majority of the Irish people, and because it is at the same time inseparable from the national question. This quite apart from the Irish being more passionate and revolutionary in character than the English.

As for the English bourgeoisie, it has in the first place a common interest with the English aristocracy in turning Ireland into mere pasture land which provides the English market with meat and wool at the cheapest possible prices. It is equally interested in reducing, by eviction and forcible emigration, the Irish population to such a small number that English capital (capital invested in land leased for farming) can function there with “security.” It has the same interest in clearing the estate of Ireland as it had in the clearing of the agricultural districts of England and Scotland. The £6,000-10,000 absentee-landlord and other Irish revenues which at present flow annually to London have also to be taken into account.

But the English bourgeoisie has, besides, much more important interests in Ireland’s present-day economy.

Owing to the constantly increasing concentration of tenant-farming, Ireland steadily supplies its own surplus to the English labour market, and thus forces down wages and lowers the moral and material condition of the English working class.

And most important of all! Every industrial and commercial centre in England now possesses a working class divided into two hostile camps, English proletarians and Irish proletarians. The ordinary English worker hates the Irish worker as a competitor who lowers his standard of life. In relation to the Irish worker he feels himself a member of the ruling nation and so turns himself into a tool of the aristocrats and capitalists of his country against Ireland, thus strengthening their domination over himself. He cherishes religious, social, and national prejudices against the Irish worker. His attitude towards him is much the same as that of the “poor whites” to the “niggers” in the former slave states of the U.S.A. The Irishman pays him back with interest in his own money. He sees in the English worker at once the accomplice and the stupid tool of the English rule in Ireland.

This antagonism is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power. And that class is fully aware of it.

But the evil does not stop here. It continues across the ocean. The antagonism between English and Irish is the hidden basis of the conflict between the United States and England. It makes any honest and serious co-operation between the working classes of the two countries impossible. It enables the governments of both countries, whenever they think fit, to break the edge off the social conflict by their mutual bullying, and, in case of need, by war with one another.

England, being the metropolis of capital, the power which has hitherto ruled the world market, is for the present the most important country for the workers’ revolution, and moreover the only country in which the material conditions for this revolution have developed up to a certain degree of maturity. Therefore to hasten the social revolution in England is the most important object of the International Workingmen’s Association. The sole means of hastening it is to make Ireland independent.

Hence it is the task of the International everywhere to put the conflict between England and Ireland in the foreground, and everywhere to side openly with Ireland. And it is the special task of the Central Council in London to awaken a consciousness in the English workers that for them the national emancipation of Ireland is no question of abstract justice or humanitarian sentiment but the first condition of their own social emancipation. [13] …

—–

[12] On September 18 an attack was made at a prison in Manchester in order to free 2 Fenian leaders, Kelley and Deasy. They escaped, but 5 others were captured and later sentenced to death and executed for having killed a policeman.

[13] See page 16 in Gotfred Appel: Class Struggle and Revolutionary Situation, Futura, 1971.

MESC p. 235.

MEOC p. 335.

MEOB p. 550.

The complete text can be found online at Marxist Internet Archive, MIA.